Until now I published as an author 30 books in my native language (French), including 14 science essays, 7 historical novels and 9 poetry collections (for the interested reader, visit my French blog here.

Although my various books have been translated in 14 languages (including Chinese, Korean, Bengali…), 4 of my essays have been translated in English.

The second one was :

Glorious Eclipses : Their Past, Their Present, Their Future

Translated from French by Storm Dunlop

Cambridge University Press, 2001 -ISBN 0 521 79148 0

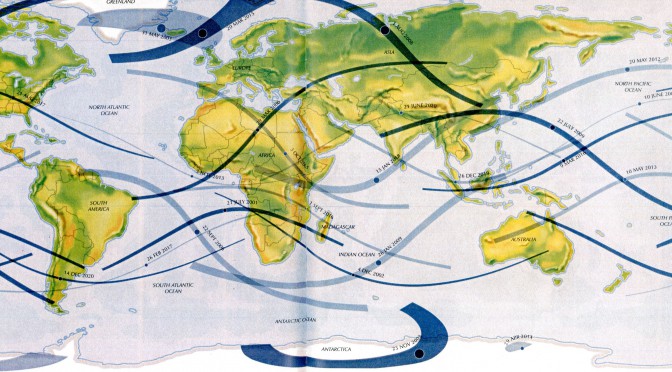

This beautiful volume deals with eclipses of all kinds – lunar, solar and even those elsewhere in the Solar System and beyond. Bringing together in one place all aspects of eclipses, it is written by the perfect team : Serge Brunier is a life-long chaser of eclipses, and internationally-known astronomy writer and photographer, whilst Jean-Pierre Luminet is a famous astrophysicist with a special interest in astronomical history. Lavishly illustrated throughout, Glorious Eclipses covers the history of eclipses from ancient times, the celestial mechanics involved, their observation and scientific interest. Personal accounts are given of recent eclipses – up to and including the last total solar eclipse of the 20th century : the one on August 11th 1999 that passed across Europe, Romania, Turkey and India. This unique book contains the best photographs taken all along its path and is the perfect souvenir for all those who tried or wished to see it. In addition, it contains all you need to know about forthcoming eclipses up to 2060, complete with NASA maps and data.

This beautiful volume deals with eclipses of all kinds – lunar, solar and even those elsewhere in the Solar System and beyond. Bringing together in one place all aspects of eclipses, it is written by the perfect team : Serge Brunier is a life-long chaser of eclipses, and internationally-known astronomy writer and photographer, whilst Jean-Pierre Luminet is a famous astrophysicist with a special interest in astronomical history. Lavishly illustrated throughout, Glorious Eclipses covers the history of eclipses from ancient times, the celestial mechanics involved, their observation and scientific interest. Personal accounts are given of recent eclipses – up to and including the last total solar eclipse of the 20th century : the one on August 11th 1999 that passed across Europe, Romania, Turkey and India. This unique book contains the best photographs taken all along its path and is the perfect souvenir for all those who tried or wished to see it. In addition, it contains all you need to know about forthcoming eclipses up to 2060, complete with NASA maps and data.

************************************************************************

EXCERPT : FOREWORD

Why should a theoretical astrophysicist, who has rarely peered through the eyepiece of a telescope, preferring to speculate on the invisible architecture of space-time by means of dry equations, be interested in eclipses, to the extent of writing a book about them?

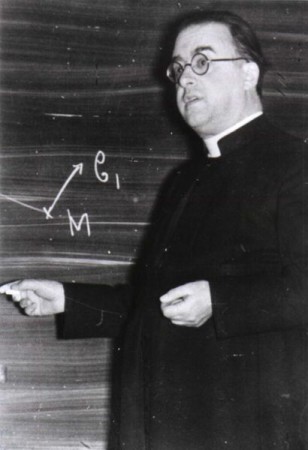

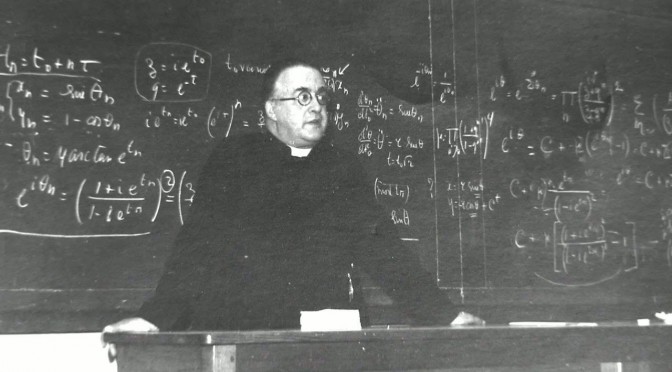

It is true that Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which has been a constant intellectual delight for me over so many years, was first proved experimentally thanks to a ‘simple’ solar eclipse. That was on 29 May 1919. But such an argument satisfies only the intellect. When it comes to the soul, it demands a greater spectacle, a more tangible emotion.

I was not yet ten on 15 February 1961, when a total eclipse of the Sun crossed the Provence where I was born. All I can recall is preparing smoked glass under the watchful eye of our schoolmistress. Clouds over Cavaillon probably spoilt the spectacle, because I have no memory of the eclipse itself…

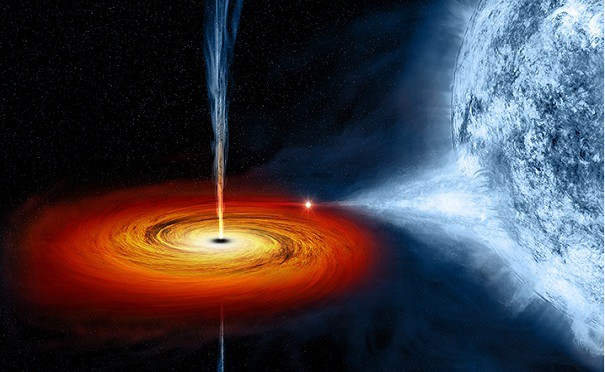

Then… then I waited nearly forty years before finally seeing a total eclipse of the Sun. That was on 26 February 1998, in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Maria, in the north of Colombia. Serge Brunier and a few other colleagues, genuine eclipse chasers, had finally convinced me that any astrophysicist worthy of the name should not ‘die a fool’! It is true that, obviously, such a recurrent and ‘nearby’ astronomical event might seem somewhat prosaic to someone who spends his life in abstract research on models of the Big Bang, black holes, and the realms of space-time.

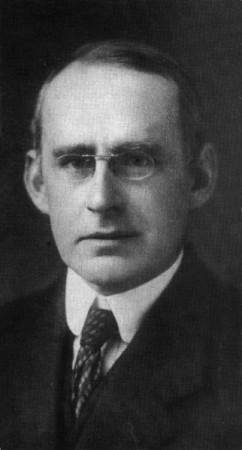

On that day, however, between 10:59 and 11:03, I experienced what John Couch Adams described so well, some 150 years before. The English mathematician-astronomer, less accustomed to handle telescopes than complex equations of celestial mechanics – he predicted the existence of the planet Neptune through calculation – witnessed a total eclipse of the Sun for the very first time in his career during the summer of 1846. He subsequently described the extraordinary emotions he felt as an astronomer – and, moreover, an experienced one – who realized that he was a novice when he discovered this astounding cosmic drama for the very first time.

The darkness that descends suddenly in the very middle of the brilliance of the day; this new light that arises from the obscurity; the planets aligned like a necklace of pearls in a configuration that is never seen by night; and the Sun’s flamboyant corona…

These few minutes in which time seems suspended, create the almost palpable feeling of being, transiently, part of the invisible harmony that rules the universe. It is as if a sudden opening in the opaque veil of space allows our inner vision to reach into the otherwise hidden depths of the cosmos, giving us humans – mere insignificant specks of dust – an all-too-brief instant to see the other side of the picture.

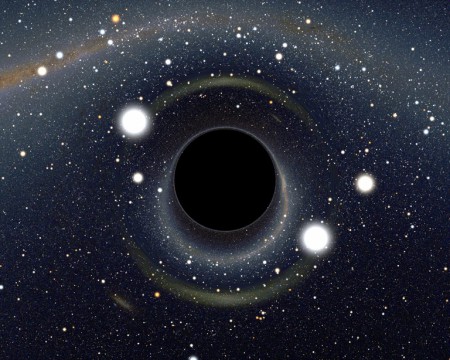

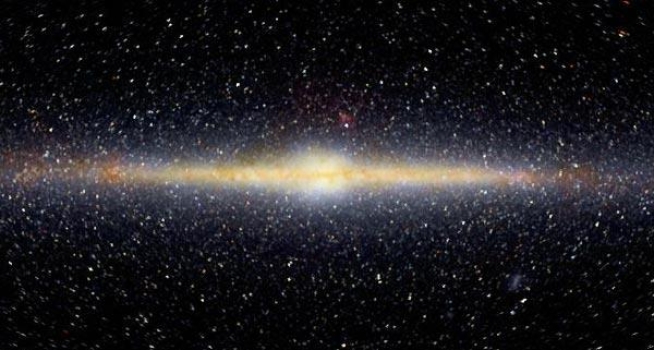

To me, the invisible is not restricted to dark objects that our telescopes cannot detect. It is also, and in particular, the secret architecture of the universe, the insubstantial framework of our theoretical constructs. I have always been moved by black. Not black as in absence, but rather black as revealing light. According to the painter Francois Jacqmin ‘Shadow is an insatiable star-studded watchfulness. It is the black diamond that the soul perceives when the infinite rises to the surface.’ Astrophysics and cosmology team with examples where black is all-important. It is in the black of the night that one sees stars, or, in other words, that one perceives the immensity of the cosmos. This same night-time darkness reveals the whole evolution of the cosmos, and the finite nature of time. The mass of the universe is largely dominated by dark matter; massive, non-luminous objects, which through their gravitational attraction govern the dynamics of the cosmos. As for black holes, the epitome of invisibility, they are perhaps secret doorways opening onto other regions of space-time.

Another aspect of eclipses enthrals me: their historical and cultural dimension. I have always been attracted by the way in which different forms of human invention interact. Science, despite being an effective and rational approach to truth, nevertheless remains incomplete. Art, philosophy, and the comparative study of traditions, myths and religions, are all complementary approaches that are indispensable for anyone who wants to gain a greater insight into where they fit in the cosmic scheme of things.

In unfolding the story of people, their civilizations, and their relationships with heavenly phenomena, one cannot but be fascinated to see how past eclipses have influenced their course. The impression of a supernatural power engendered by the sudden disappearance of the Sun or the Moon has often struck human beings, frightened by an apparently hostile and incomprehensible nature, to the extent of changing their behaviour.

That’s enough. My colleague, Serge Brunier, and I decided to write a book that alternated between these ‘two voices’. After all, the various types of eclipses are created by the Earth and the Moon taking it in turn to pass in front of each other beneath the blazing Sun…

Eclipses are a benign contagious virus, which once it has infected you, recurs at intervals. Which is why, for the eclipse of 11 August 1999, I went deep into the Iranian desert, to be (almost) certain of finding a sky devoid of clouds.

*********************************************************************

PRESS REVIEWS

An extrordinarily beautiful book, Glorious Eclipses guides us elegantly through the history of obscurations of the sun and moon – from the ancient Chinese belief that a dragon was devouring the daytime star through current theories and on to celestial events forthcoming in the next six decades. Some of the most startling images come from the days when photography was in its infancy and astronomers still made drawings of eclipses.

Scientific American, June 2001

Darkness at noon

At first sight, this is the ultimate eclipse book. Oversize, well-produced photographs in a large-format book are accompanied by interesting text covering a wide variety of eclipses phenomena. The partnership of an astronomer writer/editor and a professional astronomer, albeit a cosmologist, successfully brings the beauty of total solar eclipses to the fore.

Although the writers alternate, the difference is not jarring, perhaps thanks to the expert translator, Storm Dunlop. In a chapter entitled “The great cosmic clockwork”, Serge Brunier, long-time editor of the French popular astronomy journal Ciel et Espace, discusses the many kinds of eclipses and occultations (when one astronomical body occults, or hides, another). He even includes the eagerly awaited 2004 transit of Venus – the passage of Venus across the face of the Sun. This will be the first transit of Venus visibe from Earth since 1882.

The reproduction of photographs in 25 cm x 35 cm format on heavy stock is outstanding. For example, we see Saturn’s rings extending across a double page for almost half a metre in a Hubble Space Telescope image. The authors justify using this image, which shows the shadow of Saturn’s satellite Titan on Saturn’s clouds, by pointing out that it corresponds to an eclipse of the Sun by Titan as seen from Saturn. It’s a pity, though, that Brunier calls himself an “eclipse chaser” – that common but misleading phrase seemps to imply that people can outrun, or even outfly, eclipses, which has never been done.

Brunier is responsible for some of the most magnificent photographs, such as one from the 1991 total solar eclipse visible from the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii, with a few telescopes in the foreground. But the image I found most arresting is not one of this; it is a wide-angle shot of the 1991 eclipse viewed through a hole in the clouds and showing the front of Reims Cathedral in the left foreground.

In his chapters on the history and cultural significance of eclipses, Jean-Pierre Luminet reproduces a remarkable set of historical images related to solar and lunar eclipses from around the world. These are no doubt related to his work on an exhibition of astronomical atlases held in Paris at the Bibliothèque Nationale in 1998.

It was good to read about myths that cast eclipses in a favourable light rather than as evil omens. Luminet also describes the history of scientific discovery through observations of solar eclipses. One example is the discovery at the 1868 total solar eclipse of the spectrum of the solar chomosphere – the layer of the Sun just above the surface that becomes briefly visible at the beginning and end of totality. The element helium was also discovered at this eclipse.

There is much that is excellent in the book. The charts of future eclipses at the end of the book are redrawn at the highest quality. Lunar eclipses are included in the text, photos and charts, looking almost as dramatic on the page as the solar ecipses, even though they are much less so in reality. As a book of history, myth, literature, photography and expeditionary experiences, Glorious Eclipses is outstanding, despite its omission of the solar research carried out at recent eclipses.

Jay Pasachoff, Nature, vol. 410, 29 march 2001.

Wonder of day turned into light

A total eclipse of the Sun is about as astonishing a treat as nature provides. For a few minutes, the Moon exactly covers the Sun, making night from day and displaying the otherwise invisible solar atmosphere. This book celebrates eclipses of both Sun and Moon (the rather less spectacular sweeping of Earth’s shadow across the lunar surface) from many directions, including the complex history of eclipse observations and their declining but still real scientific value.

Serge Brunier and Jean-Pierre Luminet are respectively a science journalist and photographer, and a senior astronomer. This book, well translated from French by Storm Dunlop, makes the most of their strengths. It displays a deep understanding of history, some gripping science and a wealth of images, both of eclipses and of the many ways in which they have been represented over the years.

(…)

If you want to take up eclipse chasing, the book’s maps of future eclipses will tell you when and where to be, and its illstrations will tell you what to expect and how to observe in safety. There are explanations of the eclipse cycle, or Saros, and of the fact that in the far future, there will be no more solar elipses as the Moon’s distance from the Earth increases.

The book also provides generous coverage of lunar eclipses and of related events such as occultations and transits. There is even space to reveal how planets in other solar systems are being detected as they eclipse their own star as seen from Earth. Eclipses still make cutting-edge science thousands of years after they first caused dismay to our ancestors.

Martin Ince, Deputy Editor, The Times Higher, March 9 2001.

Not in the shade

This attractive and beautifully illustrated book, by two Paris astronomers and dedicated eclipse-chasers, was originally published in French under the title Eclipses, Les Rendez-vous Celestes (Larousse-Bordas/HER, 1999). The present English translation is by Storm Dunlop. This book is a veritable mine of information on eclipses and is suitable for anyone who has an interest in eclipses, be they amateur or professional astronomer, photographer or historian.

The scene is set in the first chapter, which captures much of the appeal of total solar eclipses and leaves the reader in no doubt as to why eclipse chasers will travel vast distances to witness a few minutes of totality.

In chapters two and three, the historical and literary aspects of both solar and lunar eclipses are discussed. Although there is some sound history in the first of these chapters, there is also much speculation – especially with regard to such torical and literary aspects of both such diverse matters as Stonehenge, Thales, and the date of the Crucifixion of Jesus. Regrettably, there are several serious errors. Thus the “Assyrian tablet dating from the

2nd century BC” (p40) is in fact from Babylonia, several centuries after the demise of Assyria. Thucydides reports three eclipses, not just two (p43). “According to the Evangelists,” Jesus was not “crucified on a Thursday,” (p44). Chapter three contains some intriguing literary allusions to eclipses in prose and poetry – both ancient and modern.

Chapters four to seven provide the main substance of this book and are both fascinating and informative. They deal respectively with: the cause of both lunar and solar eclipses; lunar and planetary occultations and also Mercury and Venus transits; total solar eclipse phenomena; and the famous or infamous (depending on the wearher) 1999 eclipse. In particular, it is gond to see a discussion of occultations and transits – which, in a sense, are eclipses in their own right.

The final chapter contains helpful hints for observing and photographing eclipses and also a series of attractive maps showing the visibility of future solar and lunar eclipses – with special emphasis on those over the next 20 years. Unfortunately many of the individual solar eclipse maps (p156–69) are confusing; in each case the maps show “Total eclipse begins at sunrise”, “Path of totality” and “Total eclipse ends at sunset” whether the eclipse was annular or total.

Overall, this is a splendid hook, profusely illustrated.

F Richard Stephenson. Astronomy & Geophysics, 2001 December (Vol.42), 6.33