As an astrophysicist and a poet, I am apparently well-prepared to talk about cosmic poetry. However it is not so obvious. During many years I conducted these two activities quite independently – I mean scientific investigation of the nature of the universe through the study of relativity, black holes, cosmology, topology, and poetic writing. I even refuted any relationship between these two ways of apprehending the world.

I began to publish poetry 30 years ago, at the same epoch when I also published my first scientific works, however my poetic works had nothing to do with astronomy. For me, poetry had to express feelings, emotions, and subjects that cannot not be reached by rational investigation, such as love, death, beauty, loneliness, despair, and so on.

|  |

|  |

However, later on I was involved in a nice project about astronomy and poetry. My publisher asked me to collect various texts of cosmic poetry, from different epochs and different cultures. I discovered how the greatest poets like Lucretius, Dante, Omar Khayyam, Victor Hugo, Gérard de Nerval, Edgar Poe and many others, had written the deepest things about the cosmos. They proved how poetic intuition could rejoin, or even sometimes anticipate, the scientific discoveries about the nature of the universe.

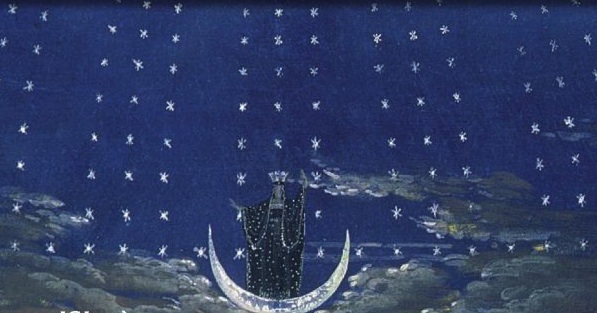

The figuration of the sky is not limited to pure astronomical representation, so imposing it is. As soon as it is a question of thinking the universe, the various disciplines of the mind are intertwined in an unravelled bond, as twenty-five centuries of cosmological questioning through science, philosophy, religion, art and poetry can testify. The universe— what there is of vaster and more subtle, of more foreign and more intimate at the same time,— is the cornerstone of creative imagination, the prototype even of any mental construction.

The specific link between the scientific and artistic approaches of the universe is manifest in the explicit representations of the cosmos : celestial charts, the design of telescopes and measuring instruments, diagrams of world systems, all translate a deep aesthetic concern. From black limestone « kudurrus » appearing in old Babylonian cosmogonies to recent photographs of gravitational lenses taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, from medieval illuminated manuscripts on the creation of the world to XVIIth century uranographic atlases set in the baroque style, from the circular perfection of Ptolemaic astronomy to the foam of baby-universes spouted out of the quantum vacuum, the will to translate some kind of celestial harmony is omnipresent among thinkers of the cosmos. Harmony directly visible in the gold nails of the firmament, but especially invisible harmony, hidden in the secret beauty of the curves and equations of cosmic mechanics. As Heraclitus said : « The most beautiful universe is a pouring out of sweepings at random. Nature likes to hide. The hidden harmony is better than the obvious. »

The term of cosmos is etymologically related to æsthetics – just as cosmetics. At the times of Homer and Hesiod, it was employed to describe the ornaments, physical or moral attraction, order, poetry, truth. Pythagoras and Plato adopted the word to indicate the whole universe. Consequently the cosmos, associated with the logos, became synonymous with a majestic and imposing universe, governed by beauty, harmony, order, and understandable to human’s mind.

But which kind of mind ? That of the astronomer, the geometer, the philosopher, or the poet? According to Plato, astronomy must be treated under the angle of mathematics and geometry, rather than under that of æsthetics or art. In Phaedrus, he even affirms: « But of the heaven which is above the heavens, what earthly poet ever did or ever will sing worthily? ».

This peremptory standpoint raises the question of literary æsthetics. Indeed, each one reminds some verses where star names resound, emphatic invocations to the moon, the sun or the Milky Way. Force is to recognize that this type of poetry uses astronomy only as an element of decoration, and makes only consolidate the judgement of Plato. I shared myself this opinion a long time. Exasperated by the amalgams of the kind : « You are an astronomer? Then you must be also a poet! », I hardly tasted this alleged « scientific poetry » presented in a didactic form, still less these lyrical flights plated on the scientist’s jargon, using of grandiloquent words with capital letters, such as Energy, Field, Quasar or Big Bang, supposed to conceal all the poetic mystery of the world. Fifteen years ago, I nevertheless devoted myself to the exploration and study of an authentic « cosmic poetry », nourished by the man’s interrogative glance on the universe [1].

This peremptory standpoint raises the question of literary æsthetics. Indeed, each one reminds some verses where star names resound, emphatic invocations to the moon, the sun or the Milky Way. Force is to recognize that this type of poetry uses astronomy only as an element of decoration, and makes only consolidate the judgement of Plato. I shared myself this opinion a long time. Exasperated by the amalgams of the kind : « You are an astronomer? Then you must be also a poet! », I hardly tasted this alleged « scientific poetry » presented in a didactic form, still less these lyrical flights plated on the scientist’s jargon, using of grandiloquent words with capital letters, such as Energy, Field, Quasar or Big Bang, supposed to conceal all the poetic mystery of the world. Fifteen years ago, I nevertheless devoted myself to the exploration and study of an authentic « cosmic poetry », nourished by the man’s interrogative glance on the universe [1].

Throughout its history, this kind of « universalist » poetry – that can be opposed to « egotistic » poetry which more exploits the register of emotion and subjectivity – is divided into two currents : that which imitates and that which invents. The first, didactic, deals with the topics provided by science and praises the scientific discoveries. Then the poet doubles the word of the scientist, making use of the lyric language and metaphor to try to differently express an emotion which does not pass by the equations. Science proposes an « external wonder » that the didactic poet tries to transform into an « internal wonder ». Except some masterpieces due to Lucretius, du Bartas or more recently Jacques Réda, it does not really succeed. Didactic poetry however gives a right reflection of the integration of the scientific knowledge in the culture at a given time. For this reason, it provides an invaluable information source for the historians and the epistemologists. A full workshop entirely dedicated to “epic science” was organized in Montreal in 2010, and a great anthology was published in 2013 (in French).

Throughout its history, this kind of « universalist » poetry – that can be opposed to « egotistic » poetry which more exploits the register of emotion and subjectivity – is divided into two currents : that which imitates and that which invents. The first, didactic, deals with the topics provided by science and praises the scientific discoveries. Then the poet doubles the word of the scientist, making use of the lyric language and metaphor to try to differently express an emotion which does not pass by the equations. Science proposes an « external wonder » that the didactic poet tries to transform into an « internal wonder ». Except some masterpieces due to Lucretius, du Bartas or more recently Jacques Réda, it does not really succeed. Didactic poetry however gives a right reflection of the integration of the scientific knowledge in the culture at a given time. For this reason, it provides an invaluable information source for the historians and the epistemologists. A full workshop entirely dedicated to “epic science” was organized in Montreal in 2010, and a great anthology was published in 2013 (in French).

The second current belongs to poets who, knowing how to see beyond the decoration, are able to reinvent the world. I call them « dreamers of the universe » – in homage to romantic German JFP Richter, currently named Jean Paul, the author of an absolute masterpiece of cosmic poetry entitled Dream of the Universe (1820). Such a poetry wants to be the widest and most intense representation of « this constantly alive and constantly changing reality, whose various parts are closely bound and mutually interpenetrate » (Henri Poincaré).

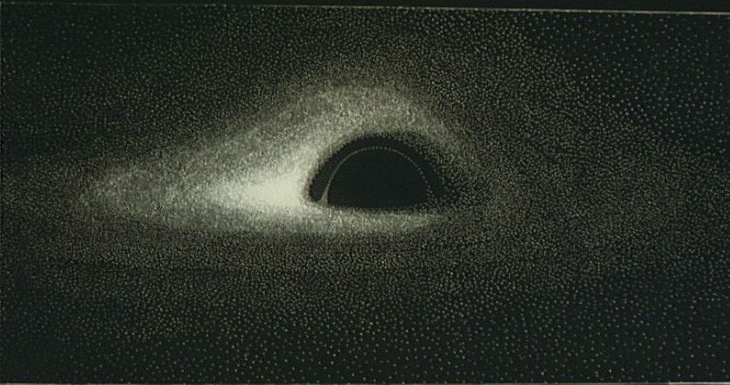

A striking illustration of my purpose are the verses of Gérard de Nerval in his Les Chimères (1854), where he closely follows a text of Jean Paul Richter about the poet’s vision of a dead star. He offers a seizing description of the whirling spiral of matter, space and time which engulf forever at the bottom of Nothingness – namely what later on astronomers will call a « black hole ». Indeed the scientific concept of black hole devourer of light and matter appeared only in the second half of XXth century. In 1979, I carried out computer simulations of the optical appearance of a black hole surrounded by a luminous gazeous disc. A virtual « photograph » of the black hole was thus produced, and appears today in handbooks of astronomy. However, to describe the scientific calculation, no caption would fit better than the Nerval stanzas (than I did not know at the time) :

In seeking the eye of God, I saw nought but an orbit

Vast, black, and bottomless, from which the night which there lives

Shines on the world and continually thickens

A strange rainbow surrounds this somber well,

Threshold of the ancient chaos whose offspring is shadow,

A spiral engulfing Worlds and Days ! [2]

The appearance of a distant black hole surrounded by an accretion disc (J.-P . Luminet, Astron. & Astrophys. 75, 228, 1979).

Thus the dreamer of the universe, enriched by his asset in all fields of knowledge, also enriched by his gaps and his doubts, by his strangely foreseeing intuition, recreates a balanced and synthetic comprehension of the world. He reconsiders the objective facts that sciences bring to him and he supplements them with intuition, he finds in them secret unitary resonances. The abysses of vastness and smallness revealed by telescope and microscope, the hidden harmony of natural laws, the various of constantly changing forms of life are worthy topics to try it. Formerly the cosmic poet dreamed on universal attraction, the primitive nebula or the cold death of the worlds; today quantum mechanics, the big bang, the black holes or the space conquest open new poetic fields.

This is precisely what the poet Francis Ponge claimed in his « Text on Electricity » (1954), a true manifesto for the revival of scientific poetry :

Here, we are back at a time very similar to that of the Cyclopes, far beyond classical Greece, far beyond Thales and Euclid, and almost at the time of Chaos. The great goddesses are sitting, once again, undoubtedly conjured up by man, but he is terror stricken when he imagines them. They are Angstrom, Light-Year, Nucleus, Frequency, Wave, Energy, Psi-Function, Uncertainty. Like the Summerian divinities, they too stagnate in a fantastic inertia but approaching them makes one dizzy. And in their aprons, written in abstract script, formulas are inscribed in advanced math. No hymn, in everyday language, could ever reach them. It would not even reach their knees. And that is why we cannot hear any of them (that is a fact), nor be tempted to compose a fitting one.

Our forms of thought, our rhetorical figures, actually date from Euclid: ellipses, hyperboles, paraboles, are also figures of that geometry. What would you want us to do? Well, exactly what we are doing, we artists, we poets, when we work well. And I do not pretend, in my case, that this has just happened. Assuredly not. It happens when we too dig into our matter: into meaningful sounds. Heedless of ancient forms and melting them back into a mass, as it is done with old statues, in order to make cannons out of them, ammunition . . . and, when necessary, new columns according to the demands of the Times.

Thus, we may perhaps, one day, create new Figures that will allow us to put our trust in the Word, in order to traverse curved Space, non-Euclidean Space.

**************************

Let me now conclude with a more personal view on poetry. For me a major point to be underlined is the close relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics and poetry : in both cases the question of the most economic language is fundamental. I mean that mathematicians and physicists try to condense their thinking into short, concise, beautiful and striking equations. It is also what the poet tries to do. As a matter of fact I am not an astronomer but a theoretician of astrophysics. Thinking about my own practice in poetry, I realised only rather recently and après-coup how my investigations about the nature of space-time, non-Euclidean geometries, black holes, topology and cosmology had a secret influence on my poetic style (if I have any syle!).

My first poems were purely linear, like time. Then, through my scientific work, I discovered how space is geometrically richer than time. Because time has only one dimension, there are only two topologies of time : linear and cyclic. Space topology is much richer. This can be transposed to poetry : the space of the poem can be considered as a topological space, which can be penetrated by differents ways of reading, different gates. It was already the case with Mallarmé and Valéry. For instance Valéry considered that the poem had to provide a « feeling of the Universe ». I practice much the idea of polysemia, namely multiplicity of meanings depending on the way a poem can be spatially read. This is clearly related to what in geometry and topology is called multiconnectedness, a property that I much exploited in my scientific researches to produce specific models for the shape of cosmic space, such as the « Poincaré dodecahedral space »[3], which is presently a good fit to observational data.

In that sense I unwillingly followed the Stéphane Mallarmé’s prescription, who wrote in 1866 « I had, with the help of a great sensitivity, understood the intimate correlation of Poetry with the Universe, and so that it is pure, I conceived the intention of leaving it from Dream and Chance and to juxtapose it with the design of the Universe. »

[1] Jean-Pierre Luminet, Les poètes et l’univers, Le Cherche-midi, Paris, 1996.

[2] G. de Nerval, Le Christ aux Oliviers, in Les Chimères, Paris, 1854. Free translation by J.-P. Luminet.

[3] Jean-Pierre Luminet et al., Nature, vol. 425, p. 593-595 (2003).

**************************

Deux poems by Jean-Pierre Luminet

Kircheriana

I see only currents of ether

boiling seas

sparkling on the placid face of the moons

viscous gold pitches melted in craters

the ebb and flow of this liquid gold

Dreamer of caves

I am the traveller of a fireproof boat

The spheres have a skeleton

perforated of cells

channels with active circulation

intended to produce the hidden virtues

Inconstant world

with momentary eruptions and vapors

whose alterations do not make any more scandal

I admire the perpetual variations

maculae on your radiant and frantic face

(trad. J.-P. Luminet)

So many questions

I’ve so many questions to ask her

what message has she got for me

if only I’d gone away

I always thought it was a game

there’s light to be had here

there’s a body in that house a warm body

waiting for something to happen

she appears at present a perfect crystalline purity

tell me what you know

of space’s crystallisation

you know that gleam in the eyes

I’ve noticed your body is different from others

the bits and pieces are cold

extraordinary thing the cold it slows down circulation

someone out there’s seen something

I should understand why for some

death yields all its meaning

that’s the enigma

a way of stopping others from coming close

a question of survival

(trad. Peter A. Boyle)

Bonjour Prof. Luminet

I live in Paris and write for the technology site Engadget. I do a bi-weekly feature called “The Big Picture,” featuring the most dramatic and artful images in technology and science.

For next week’s feature, I’d like to use your 1979 image featured in this article, of the first ever computer simulation of a black hole. I’ve always been fascinated with them, and surpringly, had never seen the image before. Many of our readers probably haven’t either, and I think they’d love it.

I’d like to get your permission to use the image, and if possible, get a higher resolution version (1,600 pixels wide would be great). Much thanks.

Hello Professor Luminet,

I am John Ryan, a New York painter. In recent years I began to write poems and pair them with paintings and drawings related to themes of personal interest, most notably the Cosmos, I am currently developing a book “Cosmic Gallery.” A prototype version is displayed on the the attached link. A recent meeting with a group of Berkeley astrophysicists, has encouraged me to incorporate commentary about the intersection of imagination with art and science especially as it relates to the Universe. I am now starting to reach out to physicists and artists who might be interested in sharing their views and contributions on the subject. In the course of my investigation, I discovered your interest in the general subject and was pleased to read your view of artists reinventing or “dreaming” of the universe. Would it be possible to talk to you directly?

Best Wishes,

John Ryan

https://walkingmanpress.com/book_library/cosmic-gallery/