Sequel of the preceding post Cosmogenesis (5) : The Order of the Creation

The Creation in the Renaissance

Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493, effectively marks the watershed between medieval scholarship and Renaissance speculation. It is the manifestation of a desire for completeness, amalgamating the principal accounts of the Creation (Genesis, Plato’s Timaeus, Hesiod’s Theogony, Ovid’s Metamorphoses) into a single, all-embracing narrative.

Ovide moralisé (Ovid Moralised) is a French text written in the late Middle Ages which regards Ovid’s Metamorphoses as having anticipated the scriptures. The early humanists inherited this view and, throughout the 16th century, the Metamorphoses were treated as a manual of morality and wisdom and subjected to numerous glosses and commentaries. This edition, published in Lyons in 1519, includes commentaries by Raphael Regius, an Italian teacher of grammar and rhetoric, and Petrus Lavinius, a Dominican monk who was part of the humanist circle in Lyon. The engraving illustrating the Creation was inspired by the Italian woodcuts in the first edition of Regius’ commentary, which was published in Venice in 1493. The fact that the artist drew the Creator as Christ rather than Jupiter shows how Ovid’s poem had been adapted to match Christian legend. Ovid, P. Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseos Libri Moralizati, Cum Pulcherrimis Fabularum Principalium Figuris, Lyons, Jacques Mareschal, 1519.

Heptaplus (1490), by the Italian philosopher Pico Della Mirandola, is a scholarly exercise in seven volumes, each of seven chapters, which attempts to synthesise the various traditions deriving from the Creation myth: that of the Platonists and the Peripatetic School, that of the Evangelists, Church Fathers and Cabbalists, and that of the Islamic philosophers such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd). In particular Mirandola tries to find a hidden meaning to the first two words of Genesis, “In principio”, using the Cabbalist method of making anagrams.

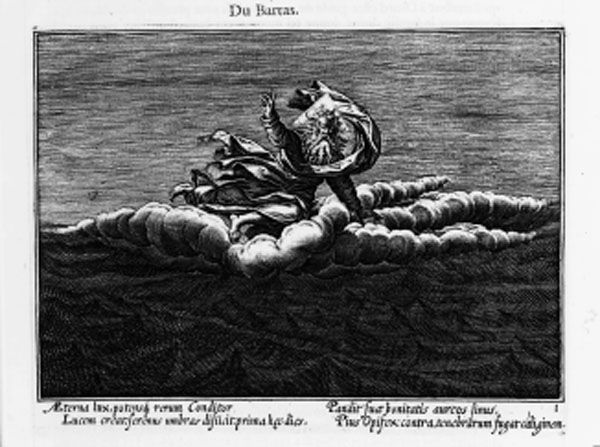

In 1578 Guillaume de Saluste, known as Du Bartas, published an epic poem based on Genesis and inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses entitled La Sepmaine (The Week). In “The First Day” Du Bartas attempts to describe chaos by using words in a confused way, using puns and antonyms:

This primordial world was form without form,

A confused heap, a shapeless melange,

A void of voids, an uncontrolled mass,

A Chaos of Chaos, a random mound

Where all the elements were heaped together,

Where liquid quarrelled with solid,

Blunt with sharp, cold with hot,

Hard with soft, low with high,

Bitter with sweet: in short a war

In which the earth was one with the sky. [i] “

First published in 1578 and re-edited, translated and annotated several times during the 17th century, La Sepmaine by Guillaume Du Bartas (1544-90) is a poetic interpretation of Genesis evoking the seven days of the Creation in the same order as the bible story. In it Du Bartas summarises contemporary scientific knowledge with numerous allusions and copious use of metaphor. Each chapter is introduced by a woodcut illustrating one of the days of the Creation. This one shows the first day. Guillaume de Saluste, seigneur Du Bartas, Les Œuvres de G. de Saluste, sr Du Bartas, reveües, corrigées, augmentées de nouveaux commentaires, Paris, Toussaint du Bray, 1610-11.

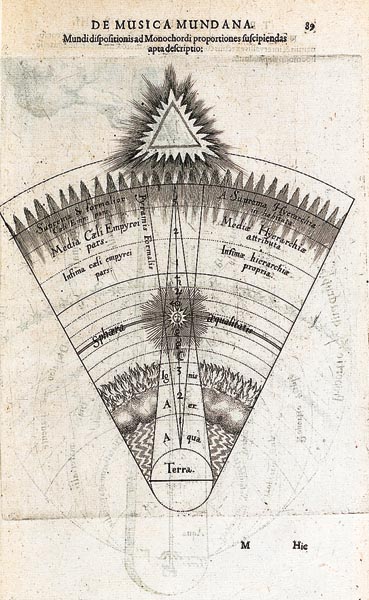

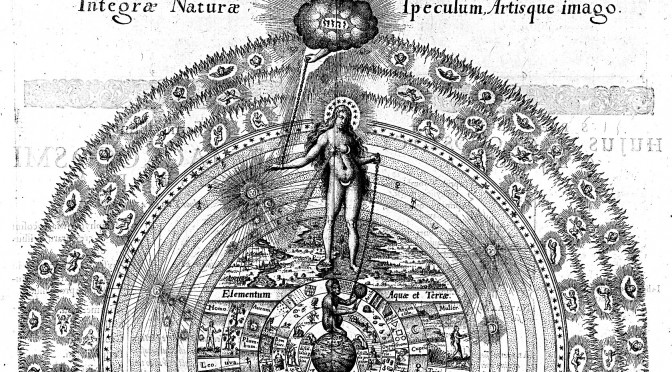

Between 1617 and 1619 the English physician and occult philosopher Robert Fludd compiled an encyclopaedia of human knowledge in four volumes entitled The Technical, Physical and Metaphysical History of the Macrocosm and Microcosm, the first volume of which is headed “The Macrocosm Metaphysics & Cosmic Origins”. The diagram in fig. 241 is an example of the curious mixture of science and occultism to be found in Fludd’s account of the Creation.

In this diagram by Robert Fludd the universe is divided into two levels: the plenum, containing the four elements and the creatures which inhabit them, below and the celestial world, kingdom of the gods, above. This distinction derives from Plato’s Timaeus, in which he describes the physical world (the lower world of “becoming”) as an imperfect copy of the ideal world (the upper world of “being”). The opposite poles of this divided universe are materiality (the earth) at one extreme and spirituality (the throne of God, represented by a burning triangle symbolizing the Holy Trinity) at the other. A “formal pyramid” (Pyramis Formalis) with its base beneath the throne of God demonstrates how abstract harmony diminishes across the spheres, reaching zero at the earth’s surface. Conversely, a “material pyramid” with its base at the center of the earth reaches a point at the highest sphere. Between God and the earth the universe is absolutely symmetrical; the three “hierarchies” of angels balance the three elements above the earth (water, air and fire). The two levels of existence, spirituality and materiality, are in harmony: one increases as the other decreases, maintaining perfect equilibrium along a plane called the “sphere of equality”, which passes through the sun’s orbit – the sun supposedly comprising an intellectual dimension and a physical dimension in equal proportions.

Robert Fludd, Utriusque Cosmi, Majoris Scilicet et Minoris, Metaphysica, Physica atque Technica Historia, Oppenheim, 1617-19, 4 volumes

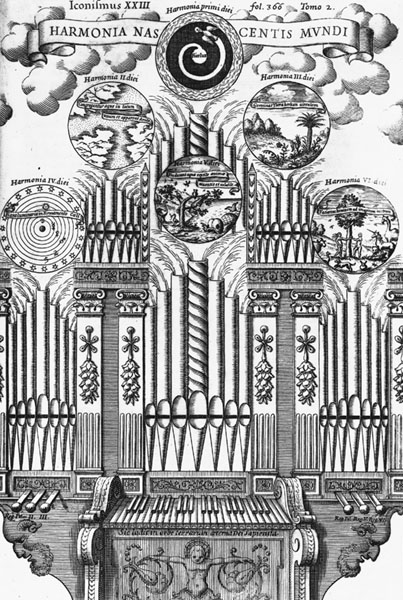

Even more extravagant is the “harmony of the world’s birth” described by the German Jesuit and encyclopaedist Athanasius Kircher, who wrote books on a variety of subjects (see fig. 244). His Musurgia Universalis, published in 1650, is in many ways reminiscent of Fludd’s Utriusque Cosmi and Kepler’s Harmony of the World and its ambitious title, The Universal Book of the Muses, immediately declares Kircher’s completist intentions. In a lengthy chapter he gives his own version of the Creation story in musical terms, comparing the world to an organ operated by God and thereby placing himself in the tradition deriving from Pythagoras and Plato, who saw the cosmos as a harmonious whole consisting of “discordant components”.

Regarded during his life as “a phoenix among scholars”, the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher studied almost every field of contemporary knowledge including astronomy, optics, geology, music, magnetism, hieroglyphics, alchemy and cabbalism. His Musurgia Universalis (Universal Book of the Muses) of 1650 is a musicological treatise in which he amalgamates 16th and 17th century Italian and German compositional methods, introduces the concept of musica patetica (music which expresses the emotions) and invents a method of classifying musical styles according to their social and ethnic characteristics. But to Kircher music was above all a branch of mathematics: musical harmony was an expression of cosmic harmony, which in turn reflected the archetypal harmony of God. This engraving illustrates Kircher’s musical vision of the hexameron in which the world is compared to an organ operated by God. In the uppermost circle the “Harmony of the First Day” is represented by Holy Spirit uttering the words “Let there be light”; each of the following days is related to a different harmony.

Athanasius Kircher, Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni in X Libros Digesta, Rome, estate of F. Corbelletti, 1650.

Reference

[i] Guillaume de Saluste, seigneur Du Bartas. La Sepmaine, Société des textes français modernes, 1994, pp. 12-13.

******************************************************************

Fantastic, I love this.