Sequel of the preceding post Cosmogenesis (9) : The Big Bang Discovery and End of the Cosmogenesis Series.

According to modern physics the universe has undergone a gradual process of expansion and cooling ever since the big bang; at the same time increasingly complex physical structures have evolved. The history of the universe can conveniently be divided into two main periods: the first million years (infancy) and the remaining 15 billion years (maturity).

The Infant Universe

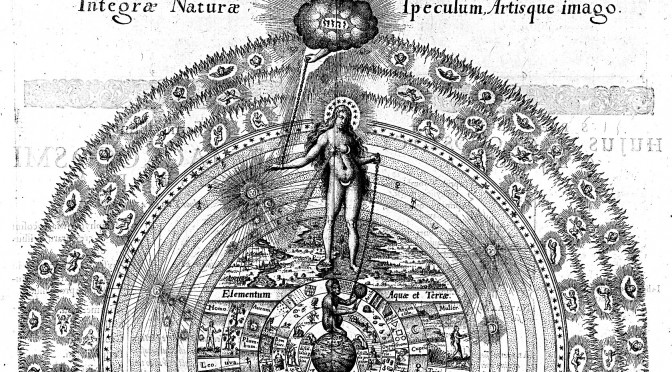

Artistic view by S. Numazawa.

During the Planck era, time and the dimensions of space as we know them were so intimately linked as to be practically indistinguishable. Various speculative theories of “quantum cosmogenesis”, as yet in their infancy, attempt to explain how our universe emerged at the end of the Planck era. Some physicists refer to its “spontaneous emergence”, others to an infinite number of separate “cosmic bubbles” arising from the quantum vacuum like foam from the surface of the sea.

Between 10-43 and 10-32 seconds after the big bang the infant universe consisted of elementary particles bound by a primeval superforce. A few billiseconds later gravity separated itself from the surviving electrostrong force, which in turn, as the temperature fell to 1027 degrees, divided into the strong force and the electroweak force. Recent experiments in high energy physics suggest that these “symmetry breakdowns” had spectacular consequences: the appearance of strange objects; “topological defects” such as “cosmic strings”; even the onset of “inflation” – a very short period during which the universe grew immeasurably. The fundamental constituents of matter – quarks, electrons and neutrinos – also appeared at this time.

10-11 seconds after the big bang the temperature of the universe had dropped to 1015 degrees and the electroweak force split into an electromagnetic and a weak force, thus establishing the four fundamental forces and fixing the physical conditions for the formation of complex structures.

10-6 seconds after the big bang all quarks were “linked” in threes by the strong force to form the first nucleons, i.e. protons and neutrons. By this time the temperature had fallen to a billion degrees as the universe continued to expand. As particles became more widely spaced, they collided less frequently but one hundred seconds or so later the crucial process of nucleosynthesis began. Neutrons and protons combined to form the simplest atomic nuclei: hydrogen, helium and lithium (in various isotopes). Most of the universe, however, remained as isolated protons, i.e. as hydrogen nuclei.

Nucleosynthesis took place only for a very short time: the universe was cooling so rapidly that there was only time for the lightest elements to form. These therefore constitute 99 per cent of the visible matter in the universe today (75% hydrogen and 24% helium). The remaining one per cent, consisting of heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, would not be created until billions of years later, when the stars were formed.

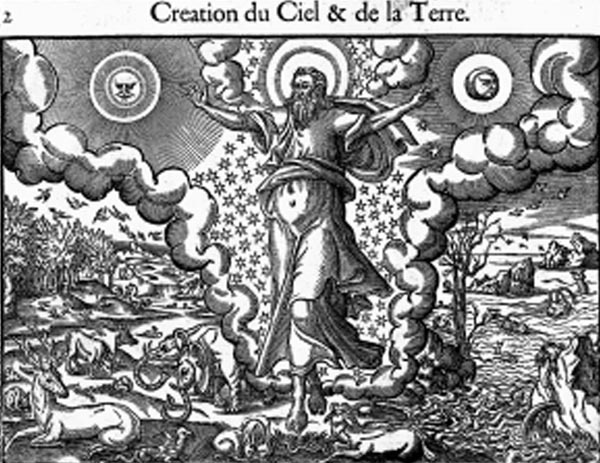

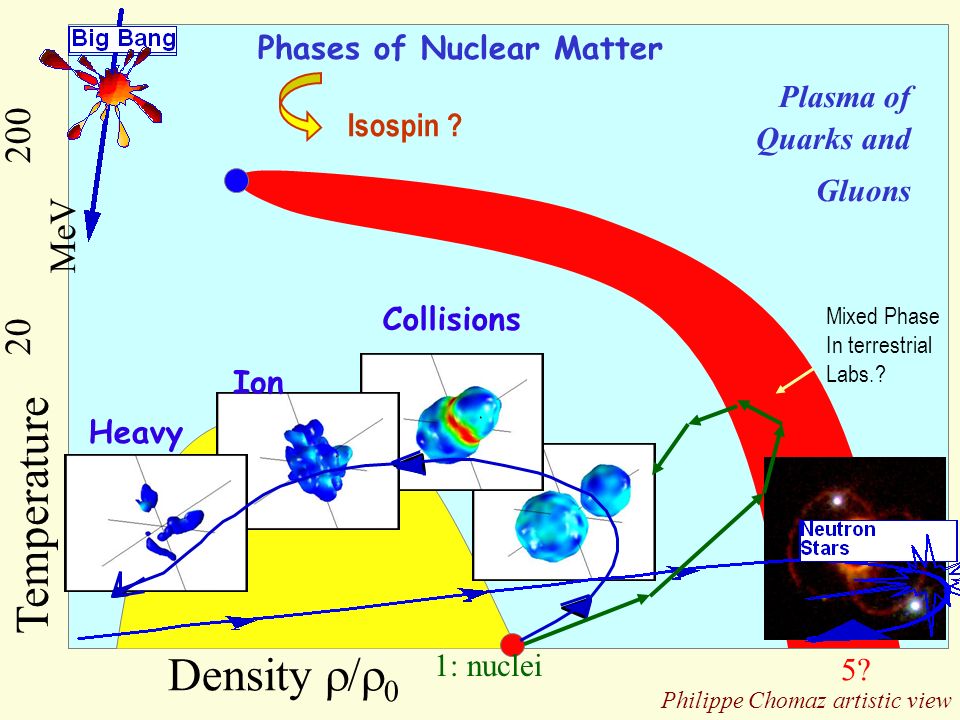

Montage by Philippe Chomaz (GANIL)

Until it was 300,000 years old the universe remained opaque; in other words it emitted no radiation: the density of electrons prevented photons from moving freely. But the universe, consisting of a “soup” of particles and radiation, continued to cool and expand until, at 3,000 degrees, it became transparent and emitted its first electromagnetic signal in the form of what we now detect as cosmic background radiation.

A million years after the big bang the first atoms were formed, when electrons were captured by hydrogen and helium nuclei, and these atoms combined into molecules to create vast clouds of hydrogen, out of which stars would later emerge. Continue reading Cosmogenesis (10) : A Modern Account