Sequel of the previous post Geometry and the Cosmos (2): From the Pre-Socratic Universe to Aristotle’s Two Worlds

Ptolemy’s Circles

Any model of the universe must incorporate the mechanisms determining the motion of the planets and other celestial bodies. From Plato and Aristotle to Kepler, astronomers could not imagine the universe governed by shapes other than circles and spheres, the only geometric forms that could possibly represent divine perfection. This constraint forced them to devise extremely complex systems which would “fit the facts”, in other words account for the apparent movements of the planets and stars as observed from the earth while conforming to the ideological demands of the concept of universal harmony.

Despite the ingenuity of astronomers like Euxodus (see previous post), their circular systems did not accurately describe the complex movements they had observed: the planets accelerated and decelerated and even occasionally went back the way they had come. Moreover, they did not account for the changes in brightness of the planets, which suggested variations in their distance from the earth that were incompatible with the idea that they travelled in circles centred on or near the earth.

How could Aristotelian cosmology be reconciled with astronomical observation? The most elaborate attempt to do so was made by Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus) in the second century AD. In his Syntaxis Mathematicae, better known by its Latin title Almagest, the Alexandrian thinker succeeded in explaining the motion of each celestial body by a system of extremely elaborate mathematical constructs.

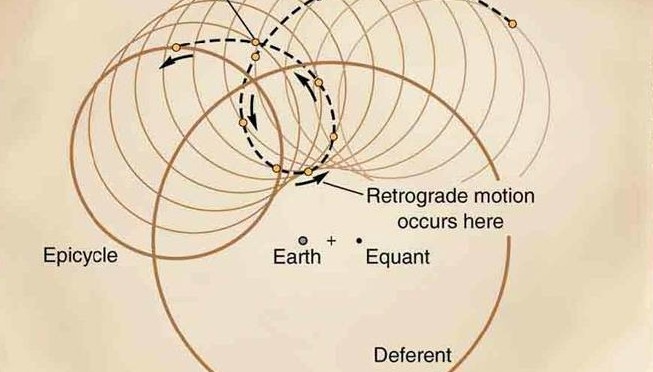

Ptolemy adopted the concept of a stationary earth and celestial bodies which could move only in circles. But he multiplied the number of circles and offset them one against the other, proposing complex and ingenious interactions between them. The circle in which a planet moves, called its epicycle, no longer had the earth at its centre as in Eudoxus’ theory, but itself revolved around another circle, called the deferent (or eccentric circle if its own centre is offset from the earth’s position). This theory enabled Ptolemy to “fit the facts” without departing too far from Aristotelian philosophical principles and it survived for 1,500 years — longer than any other idea in the history of science – until the discovery of elliptical orbits by Kepler.

The Ptolemaic system was based on three geometric patterns: the epicycle, the eccentric circle and the equant. The epicycle had been invented in the third century BC by Apollonius of Perga, a brilliant mathematician whose most famous work is a treatise on conical sections (ellipses, parabolas and hyperbolas), and developed by Hipparchus a century later.

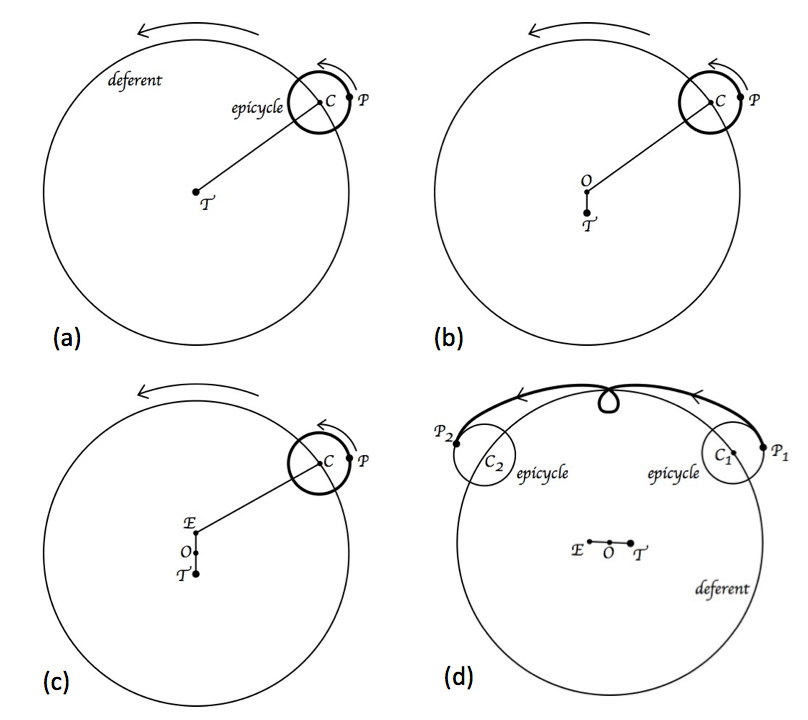

(a) Epicycle : a planet P rotates in a small circle (epicycle) whose centre (C) is simultaneously moving along the circumference of a large circle, known as the deferent, with the earth (T) at its centre.

(b) Eccentric Circle : the earth is offset from the centre (O) of the deferent. This model breaks the Aristotelian rule which states that the earth must be at the centre of the cosmos.

(c) Equant : despite its complexity, the eccentric circle model does not provide a sufficiently accurate explanation of the apparent motion of the planets. Ptolemy therefore postulated an equant point (E) about which the centre of the epicycle (C) rotates. Both the geometric centre of the deferent (O) and the centre of motion are now offset from the earth’s position (T).

(d) Final Model : the Ptolemaic model plots the motion of the planets according to this sytem, but it was so complicated that it was not fully understood by Western civilisation until the 15th century.

Ptolemy proudly defended its complexity: “We must as far as possible apply the simplest hypotheses to the movements of celestial bodies but, if these are inadequate, we must find others which explain them better.” (Almagest, XII, 2) – a statement which placed him firmly in the vanguard of modern scientific thinking.

Nevertheless, the system of epicycles and eccentric circles suggested that the earth was not exactly at the centre of the cosmos and Islamic astronomers raised several objections to this infringement of Aristotelian harmony. It was the existence of an equant point offset from the earth that particularly preoccupied later scientists. Copernicus, for example, in his De Revolutionibus announced his intention to rid the celestial model of this “monstrosity”. Continue reading Geometry and the Cosmos (3) : from Ptolemy’s circles to Inflationary Cosmology