Introduction

The regularity of so much celestial activity has led many cultures to base their models of the universe on concepts of order and harmony. Around the Mediterranean it was the Pythagoreans who first expressed the idea that the universe is characterised by proportion, rhythm and numerical patterns. Plato’s hypothesis was of an organised cosmos whose laws could be deciphered, explained in geometric terms.

The history of physics is nothing other than the story of man’s desire to uncover the hidden order and harmony of things. The most ambitious physicists have attempted to unify apparently discrete phenomena: Galileo with terrestrial and celestial laws; Newton with gravity and the movement of celestial bodies; Maxwell with magnetism and electricity; Einstein with space and time; today’s physists with gravitation and microphysics.

But, as Heraclitus said as long ago as 500 BC, “Nature loves to hide.” Indeed advances in geometry and mathematics have led to new theories of the cosmos which we are unable to comprehend. They provide only abstract images, which do not allow us to visualise the structure of atoms or the dynamics of space-time or the topology of the universe in any direct sense.

It is this fundamental belief in celestial harmony – for which successive generations have found various elaborate expressions: just proportion, equation of the part and the whole, symmetry, constancy, resonance, group theory, strings -that has underlain the development of physics for the past 2,500 years.

Geometry and the Cosmos

“Geometry, which before the origin of things was coeternal with the divine mind and is God himself […], supplied God with patterns for the creation of the world.”

Johannes Kepler, The Harmony of the World, 1619.

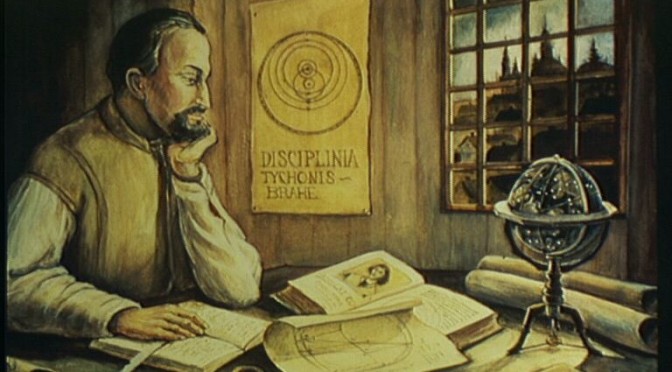

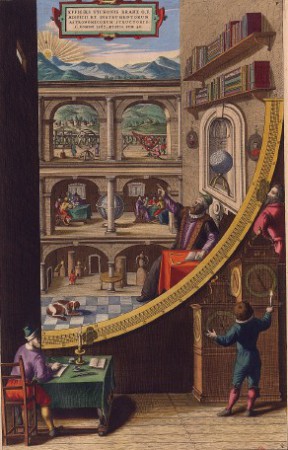

The 17th century German astronomer Johannes Kepler was undoubtedly the first to integrate man’s fascination with harmony into an overall vision of the world which can properly be called scientific. For Kepler, as for the natural philosophers of ancient Greece, the cosmos was an organised system comprising the earth and the visible stars. His avowed intention was to investigate the reasons for the number and sizes of the planets and why they moved as they did. He believed that those reasons, and consequently the secret of universal order, could be found in geometry. Kepler wanted to do more than create a simple model or describe the results of his experiments and observations; he wanted to explain the causes of what he saw. This makes him one of the greatest innovators in the history of science and it led him in particular to formulate laws of planetary motion which are still valid today.

Despite his innovative methods, Kepler wrote two studies of the cosmos in the style of the ancient Greeks: Mysterium Cosmographicum (The Secret of the Cosmos) in 1596 and Harmonices Mundi (The Harmony of the World) in 1619. At this turning point between ancient and modern thinking Kepler was steeped in a tradition which connected cosmology explicitly with the notion of divine harmony. But what Kepler sought to express was not the numerical mysticism of the Pythagoreans; his starting point was geometric patterns, which he saw as “logical elements”. His profound desire to devise a rational explanation for the cosmos led him to establish procedures which resembled those of modern science. Continue reading Geometry and the Cosmos (1) : Kepler, from polyhedra to ellipses