Sequel of the preceding post Cosmogenesis (5) : The Order of the Creation

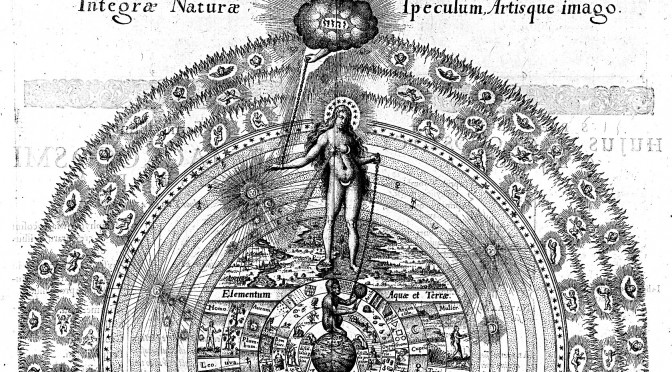

The Creation in the Renaissance

Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493, effectively marks the watershed between medieval scholarship and Renaissance speculation. It is the manifestation of a desire for completeness, amalgamating the principal accounts of the Creation (Genesis, Plato’s Timaeus, Hesiod’s Theogony, Ovid’s Metamorphoses) into a single, all-embracing narrative.

Ovide moralisé (Ovid Moralised) is a French text written in the late Middle Ages which regards Ovid’s Metamorphoses as having anticipated the scriptures. The early humanists inherited this view and, throughout the 16th century, the Metamorphoses were treated as a manual of morality and wisdom and subjected to numerous glosses and commentaries. This edition, published in Lyons in 1519, includes commentaries by Raphael Regius, an Italian teacher of grammar and rhetoric, and Petrus Lavinius, a Dominican monk who was part of the humanist circle in Lyon. The engraving illustrating the Creation was inspired by the Italian woodcuts in the first edition of Regius’ commentary, which was published in Venice in 1493. The fact that the artist drew the Creator as Christ rather than Jupiter shows how Ovid’s poem had been adapted to match Christian legend. Ovid, P. Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseos Libri Moralizati, Cum Pulcherrimis Fabularum Principalium Figuris, Lyons, Jacques Mareschal, 1519.

Heptaplus (1490), by the Italian philosopher Pico Della Mirandola, is a scholarly exercise in seven volumes, each of seven chapters, which attempts to synthesise the various traditions deriving from the Creation myth: that of the Platonists and the Peripatetic School, that of the Evangelists, Church Fathers and Cabbalists, and that of the Islamic philosophers such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd). In particular Mirandola tries to find a hidden meaning to the first two words of Genesis, “In principio”, using the Cabbalist method of making anagrams.

In 1578 Guillaume de Saluste, known as Du Bartas, published an epic poem based on Genesis and inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses entitled La Sepmaine (The Week). In “The First Day” Du Bartas attempts to describe chaos by using words in a confused way, using puns and antonyms:

This primordial world was form without form,

A confused heap, a shapeless melange,

A void of voids, an uncontrolled mass,

A Chaos of Chaos, a random mound

Where all the elements were heaped together,

Where liquid quarrelled with solid,

Blunt with sharp, cold with hot,

Hard with soft, low with high,

Bitter with sweet: in short a war

In which the earth was one with the sky. [i] ” Continue reading Cosmogenesis (6) : The Creation in the Renaissance