Sequel of the previous post 40 Years of Black Hole Imaging (1) : Early Work 1972-1988

First Flight into a Black Hole

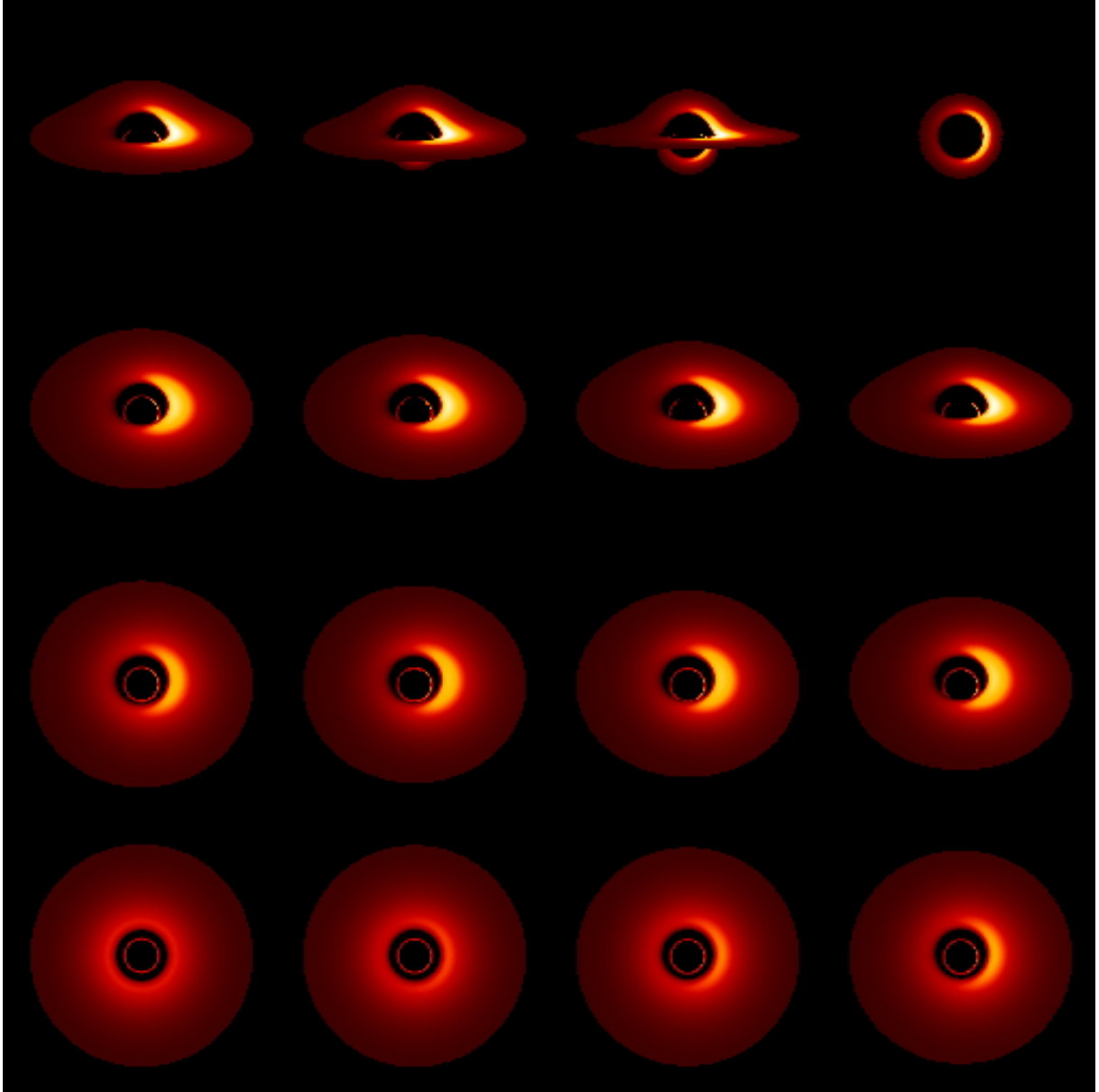

In 1989-1990, while I spent one year as a research visitor at the University of California, Berkeley, my former collaborator at Paris-Meudon Observatory, Jean-Alain Marck, both an expert in general relativity and computer programming, started to extend my simulation of 1979. The fast improvement of computers and visualization software (he used a DEC-VAX 8600 machine) allowed him to add colors and motions. To reduce the computing time, Marck developed a new method for calculating the geodesics in Schwarzschild space-time, published only several years later (Marck 1996). In a first step Marck started from my model of 1979 and calculated static images of an accretion disk around a Schwarzschild black hole according to various angles of view, see Figure 1 below.

Marck & J.-P. Luminet , 1989 (unpublished).

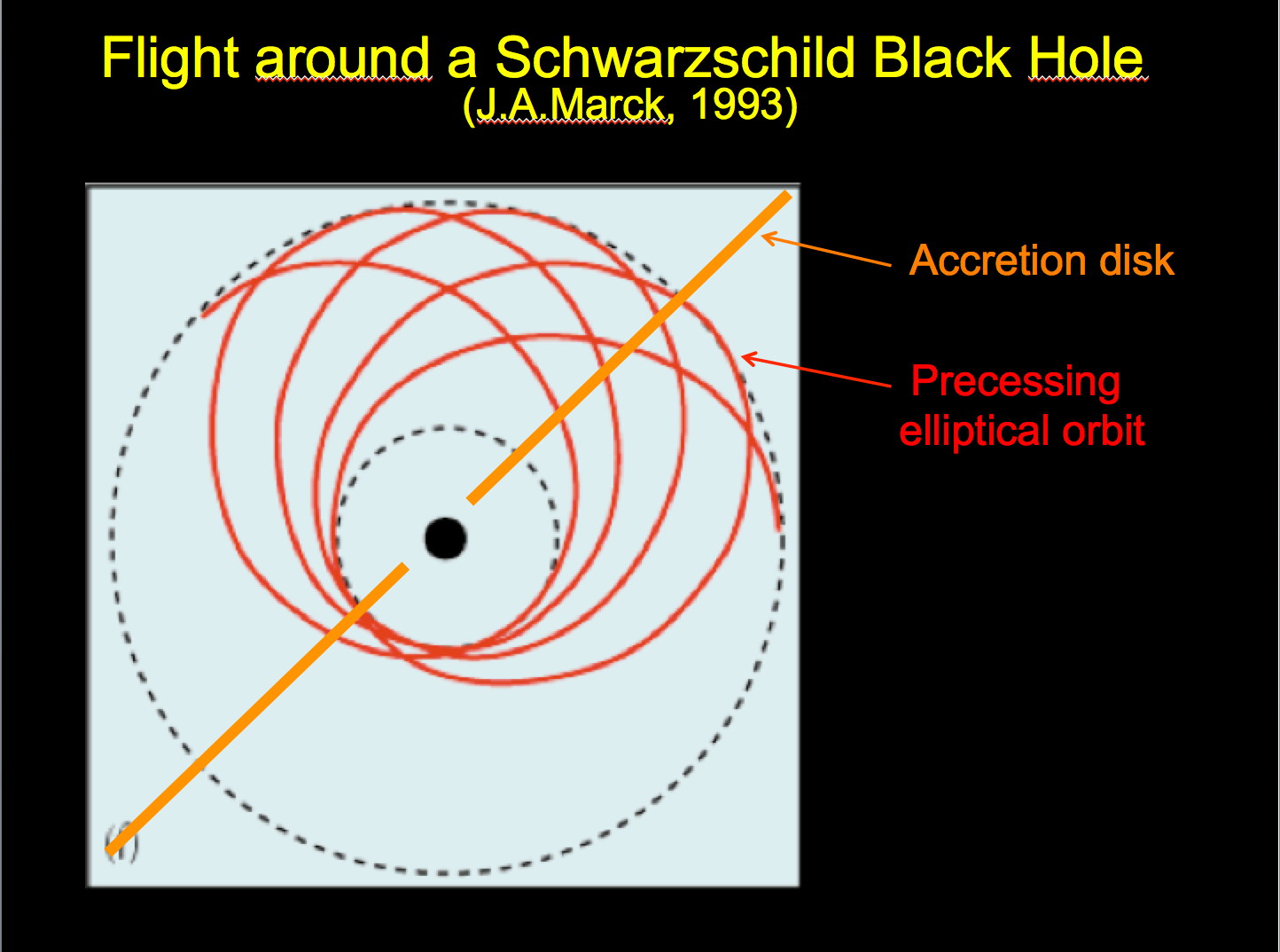

In 1991, when I went back to Paris Observatory, I started the project for the French-German TV channel Arte of a full-length, pedagogical movie about general relativity (Delesalle et al. 1994). As the final sequence dealt with black holes, I asked Marck to introduce motion of the observer with the camera moving around close to the disk, as well as to include higher-order lensed images and background stellar skies in order to make the pictures as realistic as possible. The calculation was done along an elliptic trajectory around a Schwarzschild black hole crossing several times the plane of a thin accretion disk and suffering a strong relativistic precession effect (i.e. rotation of its great axis), see figure 2 below.

Compared to my static, black-and-white simulation of 1979, the snapshot reproduced in Figure 3 below shows spectacular improvements:

Compared to my static, black-and-white simulation of 1979, the snapshot reproduced in Figure 3 below shows spectacular improvements:

above the disk’s plane. The observer uses a camera equipped with filters to convert into

optical radiation the emitted electromagnetic radiation. The arbitrary coloring encodes the

apparent luminosity of the disk, the brightest and warmest parts being colored yellow, the

colder parts red. The transparency of the disk was enhanced in order to show the secondary

image through the primary, as well as some background stars. Compared with figure 8 there

are additional distortions and asymmetries due to the Doppler effect induced by the motion of

the observer himself. As a result the region of maximum luminosity has no more the shape of a

crescent (from Marck 1991)

The full movie is available on my youtube channel :

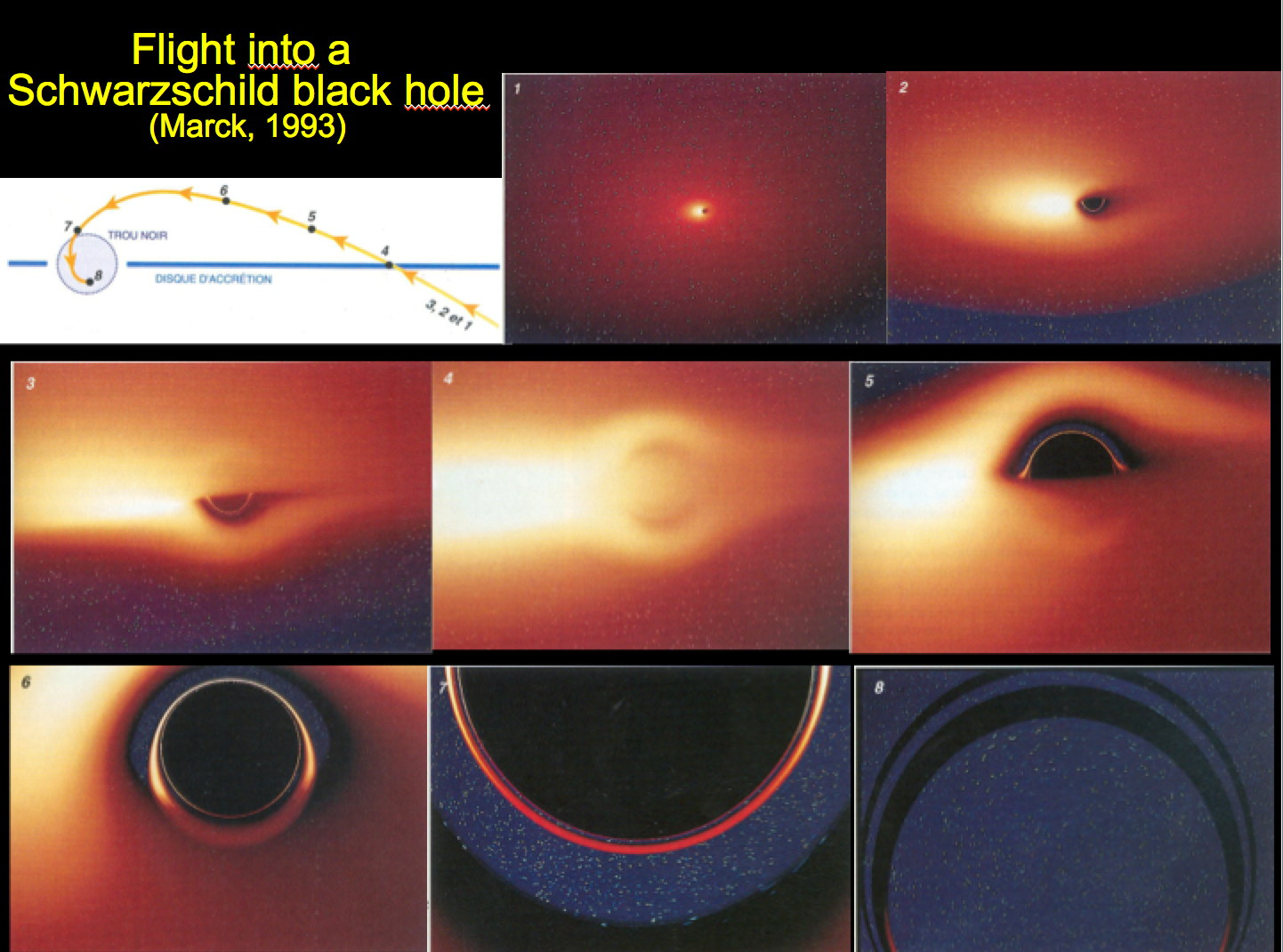

Eventually, for the needs of a videocassette shown in various international conferences and workshops, Marck calculated a new series of images as seen by an observer plunging into the event horizon of a Schwarzschild black hole along a parabolic trajectory (Marck 1994). A few snapshots were reproduced later in a special issue of a French popular magazine devoted to black holes (Marck & Luminet 1997), see figure 4 below.

trajectory plotted in the top part. Initially he is located under the plane of the disc, at a distance

1200 M from the center. He crosses the accretion disk at 39 M (4) and is very close to the

horizon at point 7. Then his speed approaches that of light and the image distortions become

quite considerable. He takes his last shot (8) inside the black hole at 0.7 M from the center,

having rotated 180 degrees to look through the rear window and see one last time several

strongly distorted images of the accretion disk and the background stellar sky (from Marck &

Luminet 1997)

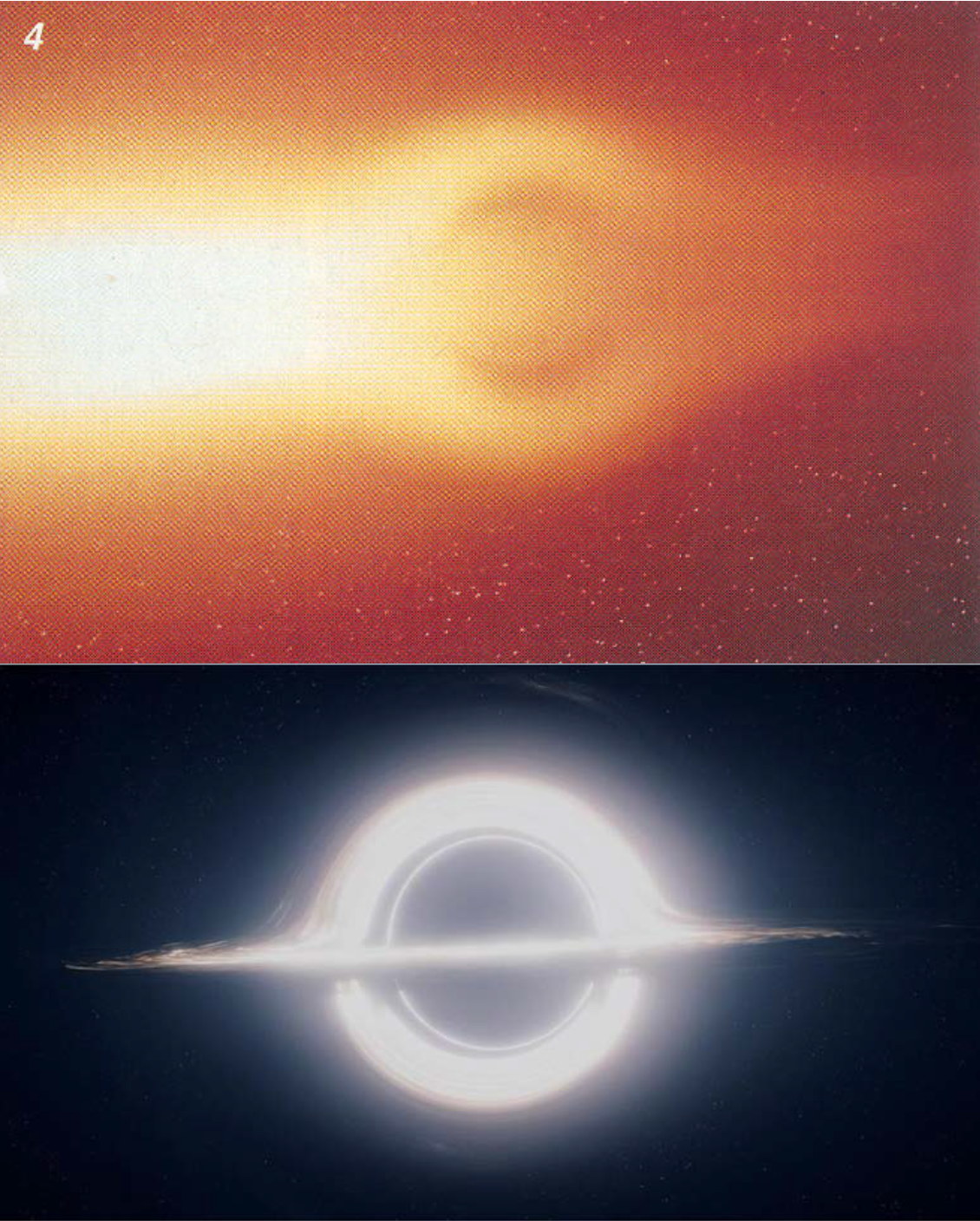

The black hole visualizations obtained by Jean-Alain Marck not only were a very significant improvement of all previous work, but they would remain unsurpassed for about twenty years, both scientifically and aesthetically. As a striking illustration, Figure 5 below compares the view of an accretion disk calculated by Marck for an observer in the equatorial plane of a Schwarzschild black hole, including all the shift effects, a truly physical model of the accretion disk and effects of light diffusion, and the famous view designed in 2014 for the science-fiction movie Interstellar, calculated with similar conditions (except the fact that the black hole was of the Kerr type, but as already pointed out the rotation does not affect significantly the asymmetry of the image). The latter was obtained by a team of 200 graphic animation experts who used a general relativistic programming code provided by their scientific advisor Kip Thorne (Kip Thorne : The Science of Interstellar, Norton & Company, november 2014). At the time it was presented by some medias as a « simulation of unprecedented accuracy » (e.g. A. Rogers, The Warped Astrophysics of Interstellar, 2014).

plane, 1994. Bottom : the same by James et al. for the movie Interstellar, 2014.

As I already commented in more details in previous posts and articles, both images correctly describe the primary and secondary images created by the gravitational field, but the second one, used for Interstellar and despite the advice of Kip Thorne (private email of 24 November 2014), left out the shift effects and the physical structure of the accretion disk on the pretext that a highly asymmetric image of the disk would be harder for a mass audience to grasp. However it is precisely this strong asymmetry of apparent luminosity that is the main signature of the black hole, the only celestial object able to give the internal regions of an accretion disk a speed of rotation close to the speed of light and to induce a very strong shift effect. In short Interstellar’s image was certainly impressive but was not really what a black hole would look like; Marcks’ image was much closer from astrophysical reality, in addition to be, in my opinion, aesthetically even more appealing.

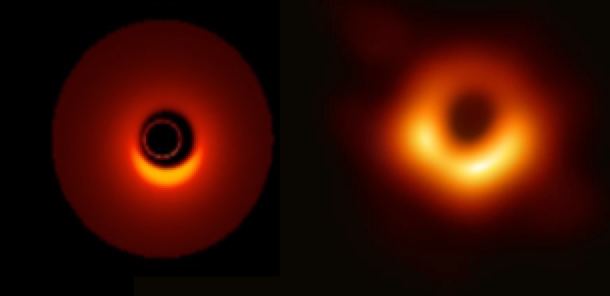

Still more impressive is the comparison between one of the snapshots from Figure 1, calculated in 1989 with an appropriate angle of view, and the telescopic image of the black hole M87* obtained in April 2019 by the Event Horizon Telescope at 1.3 mm wavelength !

The third chapter of the story is here : (3): from Kerr black holes to EHT