Sequel of the preceding post Cosmogenesis (2) : Chaos and Metamorphosis

Time and Creation

In any discussion of the creation of the world the paradoxical and complex question of temporality inevitably arises. If the Creation is regarded as an event, it must have taken place at some point in time, on a specific date. If time is regarded as a linear phenomenon, as it is in the Western world, this necessarily raises the problem whether anything existed before the Creation and, if so, what. But if time itself existed before the Creation, it cannot be part of the world as we know it – something which is difficult to imagine…

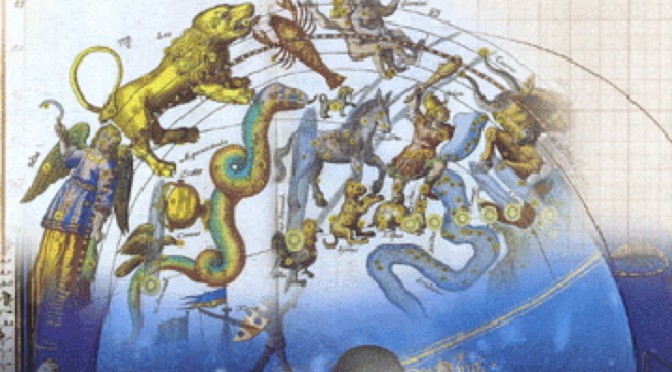

Paris, BNF, Manuscripts, Lat. 1720.

This paradox was pondered by Medieval scholars, who were forced to conclude that the world and time were created simultaneously. In the fourth century the Bishop of Milan, St Ambrose, wrote in his Hexameron: “In the beginning of time, therefore, God created heaven and earth. Time proceeds from this world, not before the world.”[1]. In the early 13th century the French philosopher and theologian William of Auvergne (also known as William of Paris) pursued a similar line of reasoning in his thinking about time: “Just as there is nothing beyond or outside the World, since it contains and includes all things, so there is nothing before or preceding time, which began with the creation of the World, since it contains all the periods of which it is comprised. This poses the question: What was before the beginning of time? or, since the word ‘before’ implies the existence of time, In the time preceding the beginning of time, did anything exist?”[2]

The same questions continue to be asked today, and scientists who are asked to give public lectures on big bang theory and the expansion of the universe commonly face two kinds of questions: “What was there before the big bang?” and “What is there for the universe to expand into?” – in other words “Did time exist before time began?” and “Is there space beyond the limit of space?” The solution of modern physics to these paradoxes is that the universe consists of space-time and therefore the creation of the world cannot be regarded as a temporal phenomenon. Continue reading Cosmogenesis (3) : Time and Creation