Introduction

Every society has a story, rooted in its most ancient traditions, of how the earth and sky originated. Most of these stories attribute the origin of all things to a Creator -whether god, element or idea.

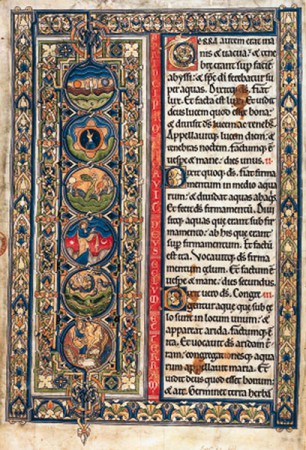

In the Western world all discussions of the origin of the world were dominated until the 18th century by the story of Genesis, which describes the Creation as an ordered process that took seven days. The development of mechanistic theories in the 18th century meant that the idea of an organized Creation gave way to the concept of evolution, and in the 19th century astrophysicists discovered that stars had their origin in clouds of gas. Big bang theory, conceived at the beginning of the 20th century, was subsequently developed into a more or less complete account of the history of the cosmos, from the birth of space, time and matter out of the quantum vacuum until the emergence of life.

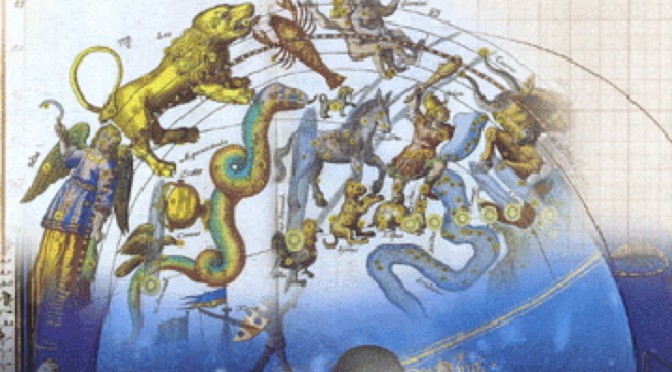

Today sophisticated telescopes show us how the first galaxies were formed, how clouds of hydrogen gave birth to stars and how the planets emerged from swirling dust. We now know that creation is still going on in our universe but the origin of life remains an enigma. How did life forms appear? The universe’s best kept secret continues to baffle scientists.

From Myth to Myth

What are the origins of the universe, of the sky, of the earth, of life, of man? These questions have given rise to many different myths and legends and continue to be the subject of intensive research by astrophysicists, biologists and anthropologists. What were once fanciful stories are now scientific models but, whatever form they take, ideas about the origins of the universe both reflect and enrich the imagination of the people who generate them. Every society has developed its own stories to explain the creation of the world; most of them are ancient myths rooted in religion.

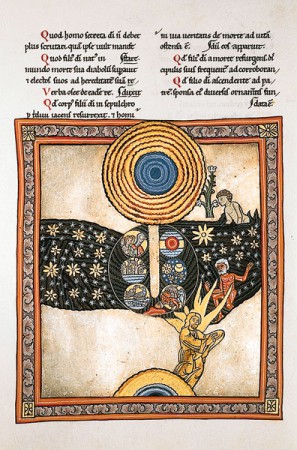

Whereas in monotheistic religions God is believed to have existed before the Creation, in most other kinds of religion the gods themselves are thought to originate from a creative element such as Desire, the Tree of the Universe, the Mundane Egg, Water, Chaos or the Void.

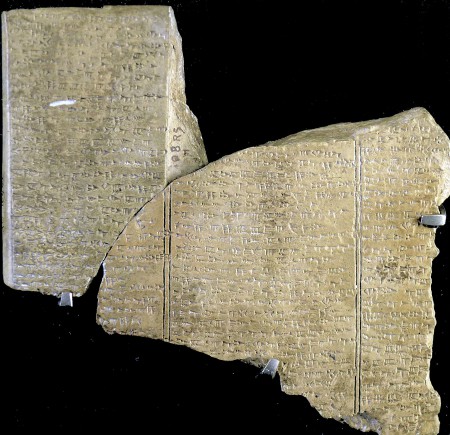

Stone from Kassite era (1202-1188 BC). Paris, Louvre.

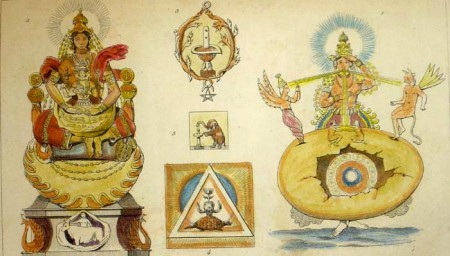

Ideas like these appear in the Rig-veda, one of the four sacred books of the Brahmins and the oldest surviving written record of Indian culture which were compiled between 2000 and 1500 BC. The Tree of the Universe, symbol of the outward growth of the world and of its organic unity, is mentioned in ancient Indian legends as well as in those of the Babylonians and Scandinavians (who call it Yggdrasil). The anthropomorphic symbol of Desire was invoked by the Phoenicians and by the Maoris of New Zealand. The Mundane Egg, from which the Hindu Prajapatis (lords of all living things) emerged, also gave birth to the gods Ogo and Nommo, worshipped by the Dogon of Mali, and the Chinese giant Pan Gu as well as constituting the celestial vault in the legend of Orpheus.

A belief in some such primordial element, of which there are traces in every culture, underlies man’s thinking about the history of the cosmos like a primitive universal symbol buried in the collective subconscious. This may explain the vague links which can always be discerned between this or that creation myth and modern scientific descriptions of the origin of the universe – for example, big bang theory. There is therefore nothing mysterious or surprising about these correspondences other than that certain ways of thinking about the world should be so ingrained in the human mind.

In fact scientific and mythical explanations of the Creation are neither complementary not contradictory; they have different purposes and are subject to different constraints. Mythical stories are a way of preserving collective memories which can be verified neither by the story-teller nor by the listener. Their function is not to explain what happened at the beginning of the world but to establish the basis of social or religious order, to impart a set of moral values. Myths can also be interpreted in many different ways. Science, on the other hand, aims to discover what really happened in historical terms by means of theories supported by observation. Often considered to be anti-myth, science has in fact created new stories about the origin of the universe: big bang theory, the theory of evolution, the ancestry of mankind. Nor are scientists above invoking mythical images in support (however tenuous) of particular lines of thought. It is therefore hardly surprising that the new creation stories developed by scientists tend to be regarded by the general public as modern myths.

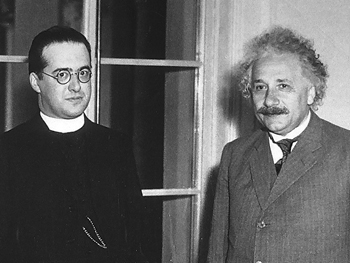

The theory of relativity, which is now the accepted framework within which both the structure and the evolution of the universe are described, is full of examples of this kind of mythologizing, despite the fact that it is less than 100 years old. Indeed the ideological basis on which Einstein built his 1917 model of a static eternal universe was partly philosophical; in order to complete the structure, he had to invent a factor called the “cosmological constant” and incorporate it into his general theory of relativity. The discovery that the universe was expanding meant that Einstein’s model had to be abandoned and in 1931 Georges Lemaître proposed a scientific explanation of the birth of space and time, according to which the universe resulted from the fragmentation of a “primeval atom” – a theory that recalls the ancient notion of everything hatching from a Mundane Egg. Lemaître’s model was subsequently revised and adjusted and became the basis of big bang theory.

The concept of continuous creation, which enjoyed some popularity in the 1950s, is an even more striking example of scientific myth making. Big bang theory had not yet been fully substantiated by observation and many astrophysicists were reluctant to accept some of its metaphysical interpretations. Among them were Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold, who in 1948 put forward the “steady state” theory, whose fundamental principle, known as the “perfect cosmological principle”, related back to Aristotle. He had maintained that the world was eternal and indestructible and therefore without beginning or end [De Caelo, 279b 4-283b 22.], in contradiction of Plato, who in Timaeus had expressed the idea that the world had begun and would end at a specific time. To compensate for the gradual dilution of matter that would result from the constant expansion of the universe the steady state theorists had to invoke the idea of continuous creation of matter, at the rate of one atom of hydrogen per cubic metre of space every five billion years.

In the same year the English astronomer Fred Hoyle demonstrated that the steady state model was feasible on condition that a new field (which he called simply “C” for “creation”) was added to the equation; this ad hoc invention was envisaged as a reservoir of negative energy which had existed throughout the life of the universe – i.e. for ever. The idea of continuous creation had appeared many times before (in the legends of the Aztecs, who believed that constant human sacrifices were necessary to regenerate the cosmos, as well as in the writings of Heraclitus and the Stoics, for example) and the scientific theory clearly followed this tradition. The theorists, however, had to “force” their model to fit their philosophical views by introducing imaginary processes. The discovery of cosmic background radiation in 1965 finally disproved their hypothesis and provided evidence for Lemaître’s big bang theory.

Codex of the followers of Tonatiuh, 18th century manuscript copy, Paris, BNF.

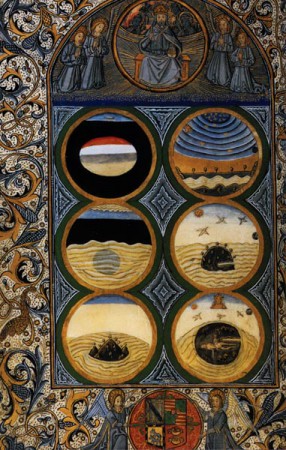

From Heptameron to Hexameron

According to Genesis the Creation lasted six days; God made the seventh day (the Sabbath) a day of rest from his work and sanctified it. The Genesis story gave rise to many commentaries, one of the most elaborate being that of St Basil of Caesarea in the fourth century AD, which is known as the Hexameron (from the Greek hexa meaning “six” and hemera meaning “day”). The ancient tradition of hexamerons, poems and stories based on the six days of the Creation, was revived by the humanists in the 16th century. In 1578 the French soldier, diplomat and poet Guillaume du Bartas published an epic poem telling of the first seven days of the world entitled Sepmaine ou Création du Monde (the French word for week, “semaine”, derives from the Latin septimana meaning “a period of seven days”). Thus the hexameron had become a “heptameron”, a term which had previously been coined in a completely different context thanks to Marguerite of Angoulême, Queen of Navarre. She wanted to write a collection of stories in the style of Boccaccio’s Decameron of c. 1353 but was so distraught at the death of her brother, King Francis I, in 1547 that she stopped writing after completing only seven of the ten “days” originally planned, with the result that the work was published under the title Heptameron in 1559.

|

|

*****************************************************

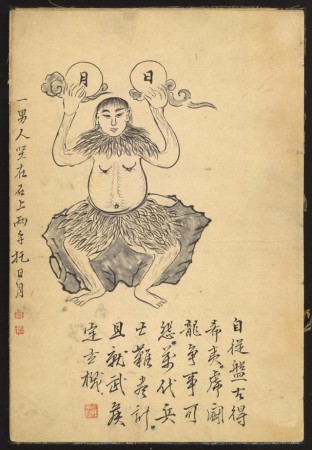

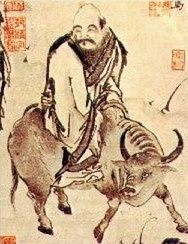

Chinese Poem

There was something formed out of chaos,

That was before Heaven and Earth.

Quiet and still! Pure and deep!

It stands on its own and does not change.

It can be regarded as the mother of Heaven and Earth.

I do not yet know its name:

I “style” it “the Way”.

Were I forced to give it a name, I would call it “the Great”.

“Great” means “to depart”;

“To depart” means “to be far away”;

and “to be far away” means “to return”.

The Way is great;

Heaven is great;

Earth is great;

And the king is also great.

In the country there are four greats and

the king occupies one place among them.

Man models himself on the Earth;

The Earth models itself on Heaven;

Heaven models itself on the Way;

And the Way models itself on that which

is so on its own.

(Lao-Tzu, Te-Tao Ching, chapter XXV, 4th century BC, trans. R. G. Henricks)

**************************************************************

Rig-veda, Ballapouram (India), c. 1730. Palm leaves. Paris, BNF

Indian Poem

In the beginning there was no existence.

Existence appeared and grew.

It became an egg.

The egg remained thus for a year.

The egg broke open.

One of its halves was of silver, the other gold.

The silver half became this earth.

The golden half became the sky.

The membrane surrounding the white of the egg became mountains,

The membrane surrounding the yolk became mist and clouds,

The blood vessels rivers.

The white became the sea

And the yolk was the sun.

(Upanishad, trans. M. Müller)

******************************************************************

Hebrew Poem

And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years: and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth: and it was so.

And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also.

And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good.

And the evening and the morning were the fourth day.

(Genesis, “The Fourth Day”, authorised version)

********************************************************************

Phoenician Poem

The atmosphere was limitless and timeless and there arose a wind which blew in a single direction. And the wind fell in love with its origin and turned back upon itself, giving birth to Desire, the origin of all things […]. Desire gave birth to Mot, a putrefied aqueous mixture which appeared in the form of an Egg – from which emerged first unconscious beings, then conscious beings and finally those who could contemplate the sky!

(Cycle of Baal, trans. A. Caquot, M. Sznycer and M. Herdner)

************************************************************************

Greek Poem

First of all there came Chaos, and after him came Gaia of the broad breast, to be the unshakeable foundation of all the immortals who keep the crests of snowy Olympos, and Tartaros the foggy in the pit of the wide-wayed earth, and Eros, who is love, handsomest among all the immortals, who breaks the limbs’ strength, who in all gods, in all human beings overpowers the intelligence in the breast, and all their shrewd planning. From Chaos was born Erebos, the dark, and black Night, and from Night again Aither and Hemera, the day, were begotten, for she lay in love with Erebos and conceived and bore these two. But Gaia’s first born was one who matched her every dimension, Ouranos, the starry sky, to cover her all over, to be an unshakeable standing-place for the blessed immortals.

(Hesiod, Theogony, trans. R. Lattimore)

Bonjour et MERCI,

Cet Article est fascinant. Que de “Richesses” !

Que de Beautés.

Viviane

Merci. J’espère que vous apprécierez autant la suite.