Continuation of previous posts Café Terrace at night, in Arles and Starry Night over the Rhône

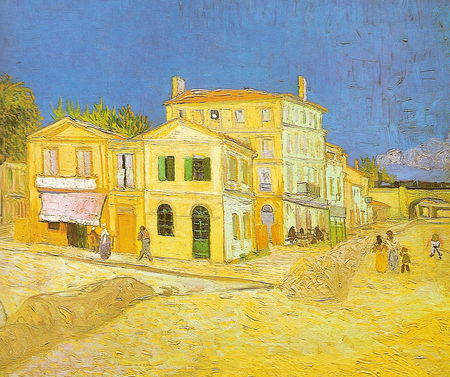

We left Vincent Van Gogh in September 1888, after he painted his Starry Night over the Rhône in Arles. On October 23rd, Paul Gauguin joined him in the “Yellow House” which he rented and where he stayed for two months. The cohabitation between these two geniuses of painting is not easy. Apart from quarrels of a domestic nature, things went badly wrong on 23 December 1888, after a discussion on painting during which Gauguin argued that one should work with imagination, and Van Gogh with nature. According to the classical thesis, Vincent threatens Paul with a knife; the latter, frightened, leaves the scene. Finding himself alone in a fit of madness, Vincent cuts off a piece of his left ear with a razor, wraps it in newspaper and offers it to an employee of the neighbouring brothel. Then he goes to bed. The police doesn’t find him until the next day, his head bloody and confused. Gauguin explains the facts to them and leaves Arles. He will never see his friend again.

The day after his crisis, Van Gogh was admitted to hospital. A petition signed by thirty people demanded his internment in asylum or expulsion from the city. In March 1889, he was automatically interned in Arles hospital by order of the mayor while continuing to paint, and on 8 May he left Arles, having decided to undergo psychiatric treatment in the insane asylum at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, a little south of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. He stayed there for a year (until May 1890), subject to three bouts of dementia, but between which his pictorial production was extraordinarily rich: he produced 143 oil paintings and more than 100 drawings in the space of 53 weeks.

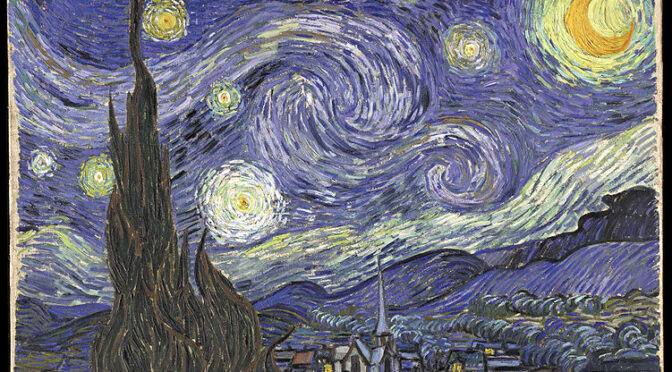

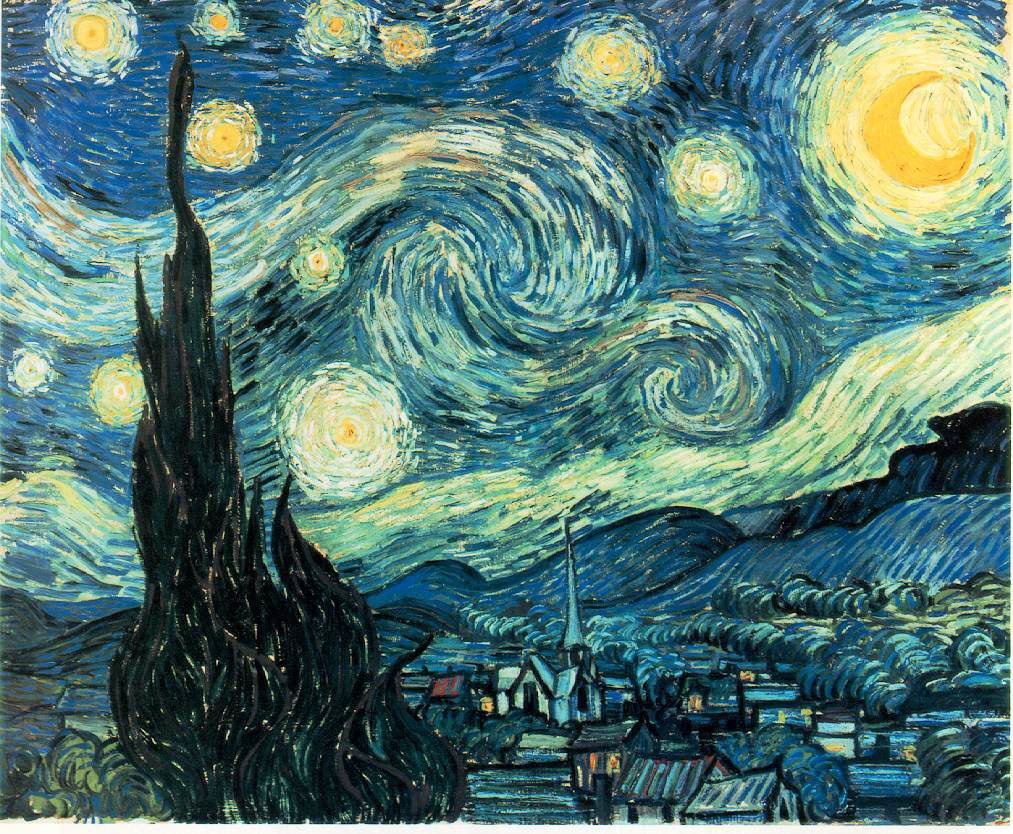

One of the key works of this period is the Starry Night, now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

I have always been fascinated by this nocturnal painting, with its tormented sky in the background, composed of volutes, whirlpools, huge stars and a crescent moon surrounded by a halo of light. In the background, a village with a church steeple overstretched towards the sky, which at first glance is thought to be the village of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Due to the position of the moon, the orientation of its crescent horns and the streak of whitish mist over the hills, one does not need to be a great expert to see at first glance that the Starry Night represents a sky just before dawn. Can we go further?

I have always been fascinated by this nocturnal painting, with its tormented sky in the background, composed of volutes, whirlpools, huge stars and a crescent moon surrounded by a halo of light. In the background, a village with a church steeple overstretched towards the sky, which at first glance is thought to be the village of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Due to the position of the moon, the orientation of its crescent horns and the streak of whitish mist over the hills, one does not need to be a great expert to see at first glance that the Starry Night represents a sky just before dawn. Can we go further?

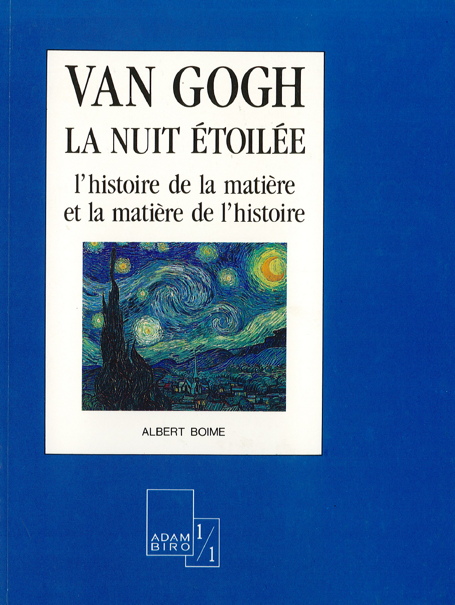

In 1995, while snooping around in a bookshop in Paris, I stumbled upon a booklet entitled La Nuit étoilée: l’histoire de la matière et la matière de l’histoire. It was the French translation of an article booklet published in 1984 in the United States by Albert Boime (1933-2008), professor of art history at the University of California at Los Angeles (“Van Gogh’s Starry Night: A History of Matter and a Matter of History, Arts Magazine, December 1984).

In 1995, while snooping around in a bookshop in Paris, I stumbled upon a booklet entitled La Nuit étoilée: l’histoire de la matière et la matière de l’histoire. It was the French translation of an article booklet published in 1984 in the United States by Albert Boime (1933-2008), professor of art history at the University of California at Los Angeles (“Van Gogh’s Starry Night: A History of Matter and a Matter of History, Arts Magazine, December 1984).

The book is fascinating. The author raises many questions which he tries to answer, notably concerning the date of the painting’s execution and the nature of the astronomical objects represented.

I said in previous posts that Van Gogh painted from nature, and therefore intended to reproduce the night skies as he saw them at the precise moment he began his paintings. I have shown how his Café le soir (Café Terrace at night ) and his Nuit étoilée au-dessus du Rhône (Starry Night over the Rhône), painted in Arles, showed the striking realism he displayed in his pictorial transposition of the firmament. This realism is less obvious in the Starry Night of Saint-Rémy, with its immense sky full of luminous objects, this moon and these far too big stars scattered among vast swirling volutes. Could his representations of the sky have slipped from realism to the wildest imagination, or even to delirium in front of the easel, to the rhythm of his own psychic deterioration?

To answer this question, we must investigate the precise genesis of the work. If, thanks to an astronomical reconstruction, we find a sky identical or close to the one represented in the painting – as was the case with his Arlesian nocturnal works – then we will have proved the realism of the painting, in addition to having dated the sketch to the day and hour.

Continue reading The Starry Nights of Vincent van Gogh (3) : The Starry Nigh at St-Rémy-de-Provence