Continuation of the previous post The Starry Night of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (1/2)

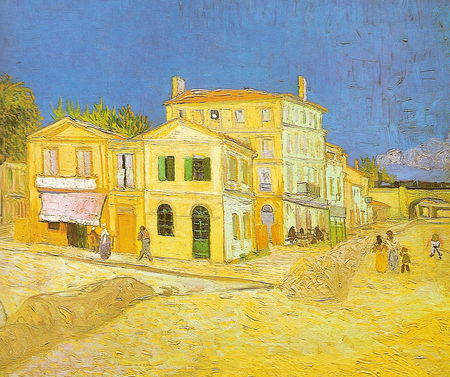

In September 2016 I went to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole monastery, a masterpiece of Provençal Romanesque art built in the vicinity of the Gallo-Roman city Glanum, south of Saint-Rémy de Provence. Part of the building remains today a psychiatric institution. Van Gogh stayed there from May 8, 1889 to May 16, 1890. On the second floor, the room where he was interned has been reconstructed.

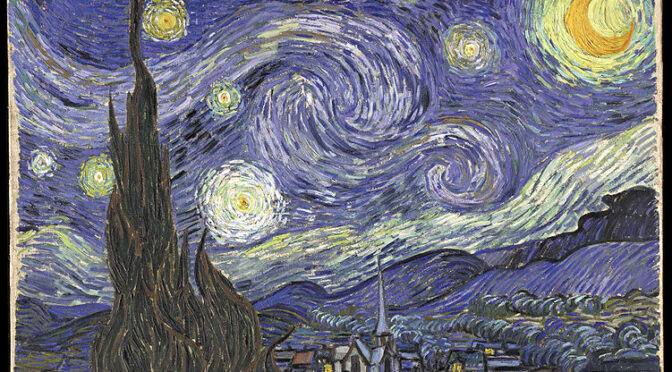

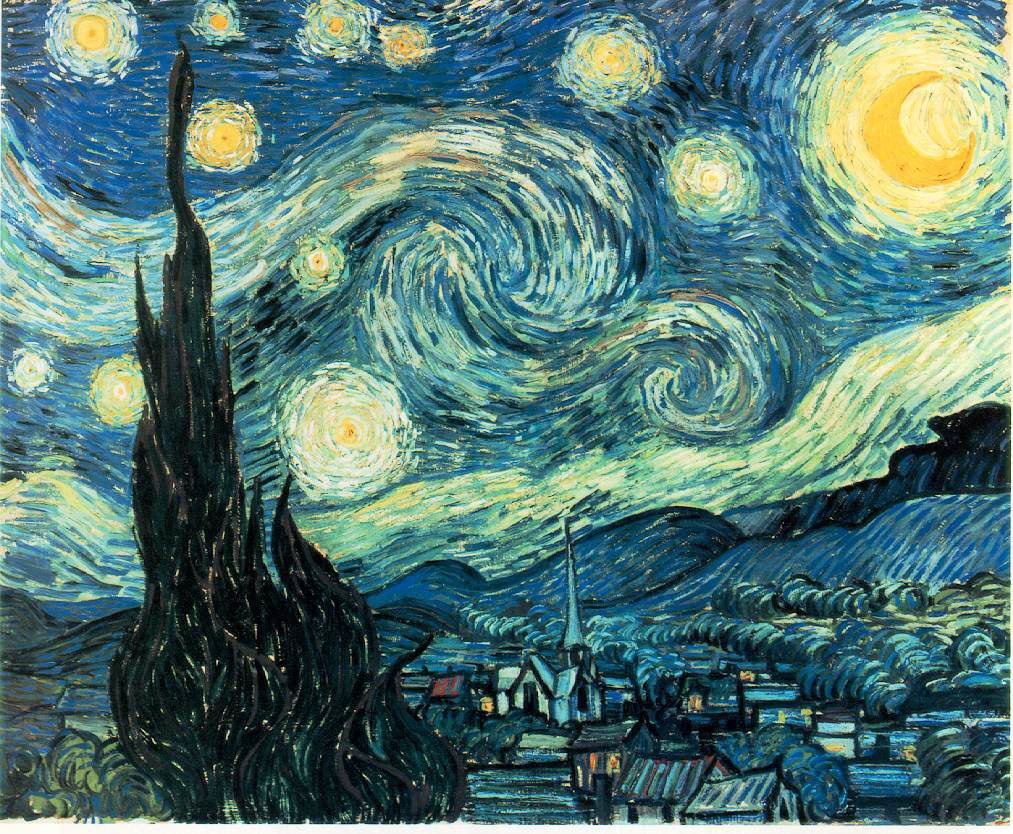

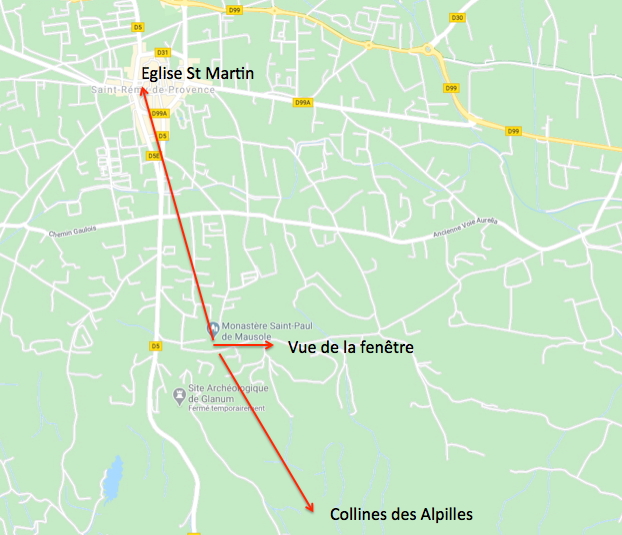

Through the window, facing east, we can see the landscape that Van Gogh could contemplate. Even if this landscape has been transformed for a little more than a century, one does not see the hills represented in his painting. In reality, there is the wall of the asylum’s park that encloses a field of wheat, which extends between the asylum and the wall. And there are no large cypress trees in sight, and even less the village of Saint-Rémy.

In fact the small chain of Alpilles is in direction of the South. As for the village of Saint-Rémy and its church tower, which is quite far away in the northern direction, it is just as invisible from the window. We conclude that Van Gogh did not paint the terrestrial part of his Starry Night from what he saw from his window.

In fact the small chain of Alpilles is in direction of the South. As for the village of Saint-Rémy and its church tower, which is quite far away in the northern direction, it is just as invisible from the window. We conclude that Van Gogh did not paint the terrestrial part of his Starry Night from what he saw from his window.

He must have gone outside. But when?

He must have gone outside. But when?

My friend Philippe André, a psychiatrist and art lover who studied Van Gogh’s correspondence in depth before publishing his novel Moi, Van Gogh, artiste peintre in 2018, wrote to me that in the first days after his internment on May 8: “At night, he is locked in his room and his equipment is under lock and key in another empty room that he was kindly allocated for this purpose. Moreover, he was very distressed and only managed to paint his own works (Sunflowers, Joseph Roulin…) or to paint very similar elements that were in the park of the asylum (Iris, Lilacs…). No strength, during those first weeks, to paint deep landscapes! “

My friend Philippe André, a psychiatrist and art lover who studied Van Gogh’s correspondence in depth before publishing his novel Moi, Van Gogh, artiste peintre in 2018, wrote to me that in the first days after his internment on May 8: “At night, he is locked in his room and his equipment is under lock and key in another empty room that he was kindly allocated for this purpose. Moreover, he was very distressed and only managed to paint his own works (Sunflowers, Joseph Roulin…) or to paint very similar elements that were in the park of the asylum (Iris, Lilacs…). No strength, during those first weeks, to paint deep landscapes! “

In fact, when I was finally able to consult Van Gogh’s complete correspondence, I read that on May 9, the day after his arrival, he wrote to his sister-in-law “Jo” (Theo’s wife, therefore):

« Although there are a few people here who are seriously ill, the fear, the horror that I had of madness before has already been greatly softened.

And although one continually hears shouts and terrible howls as though of the animals in a menagerie, despite this the people here know each other very well, and help each other when they suffer crises. They all come to see when I’m working in the garden, and I can assure you are more discreet and more polite to leave me in peace than, for example, the good citizens of Arles.

It’s possible that I’ll stay here for quite a long time, never have I been so tranquil as here and at the hospital in Arles to be able to paint a little at last. Very near here there are some little grey or blue mountains, with very, very green wheatfields at their foot, and pines. » [Letter 772]

From the first sentence it is clear that his anxiety was perhaps not so great, and the rest of the letter confirms that he did begin to paint, but without being able to go beyond the confines of his room or the small garden.

On May 23, he wrote to his brother Theo:

« The landscape of St-Rémy is very beautiful, and little by little I’m probably going to make trips into it. But staying here as I am, the doctor has naturally been in a better position to see what was wrong, and will, I dare hope, be more reassured that he can let me paint.

[…] Through the iron-barred window I can make out a square of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective in the manner of Van Goyen, above which in the morning I see the sun rise in its glory. With this — as there are more than 30 empty rooms — I have another room in which to work. […] So this month I have 4 no. 30 canvases and two or three drawings. » [Letter 776]

This shows that Vincent plans to be able to walk in the countryside outside the monastery very soon. The four canvases he has in progress were painted in the garden.

Between May 31 and June 6 he wrote to Theo asking him to send him canvases, colors and brushes, his Arles supply being exhausted. He adds :

« This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big. […] When I receive the new canvas and the colours I’ll go out a bit to see the countryside. » [Letter 777]

And finally, on June 9, after he had received the canvases and colors sent by Theo, whom he thanked warmly:

« I was very glad of it, for I was pining for work a little. Also, for a few days now I’ve been going outside to work in the neighbourhood. […]I have two landscapes on the go (no. 30 canvases) of views taken in the hills. […] Many things in the landscape here often recall Ruisdael » [Letter 779]

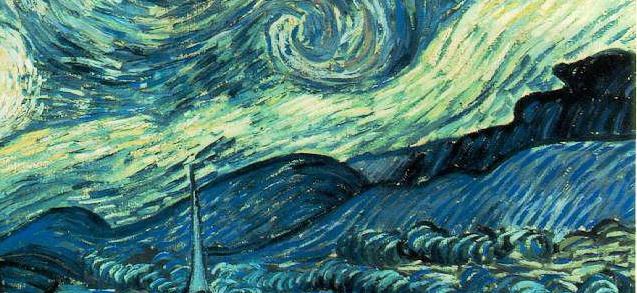

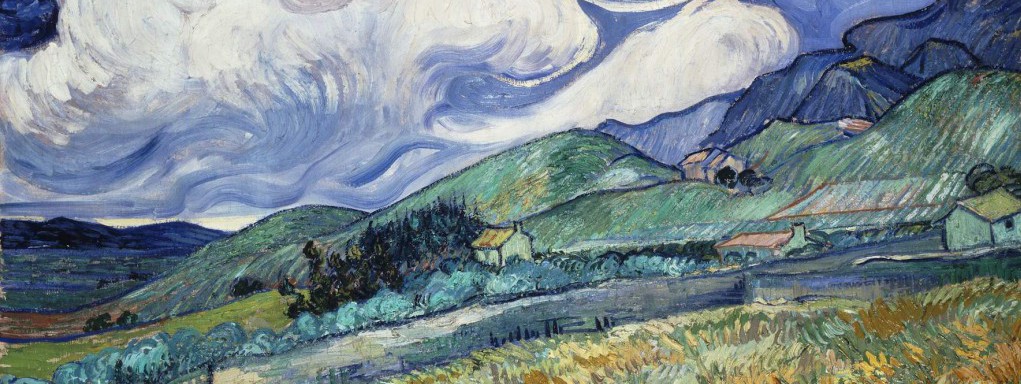

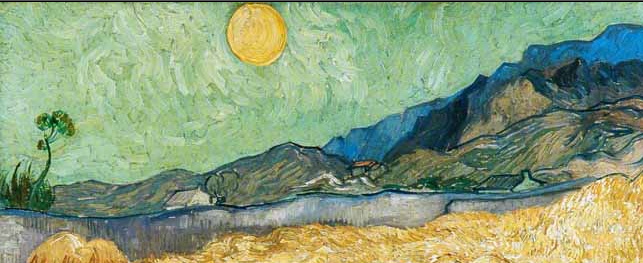

So we have the answer: it was not until the first week of June that Vincent was able to leave the monastery and start painting the landscapes seen from the surrounding countryside. Let’s start with the hills of the Alpilles. As mentioned above, they are invisible from his room, so they were necessarily painted outside. We find the same profile in other paintings of the period:

The profile of the hills is quite faithfully rendered, as I was able to see when I found the approximate location where Van Gogh set up his easel (today a field of vines):

Continue reading The Starry Nights of Vincent van Gogh (4) : The Starry Nigh at St-Rémy-de-Provence (2/2)

Continue reading The Starry Nights of Vincent van Gogh (4) : The Starry Nigh at St-Rémy-de-Provence (2/2)