As we have seen in the previous post The Starry Nights of Vincent Van Gogh’s (1): Café Terrace at night, in Arles, Vincent has therefore been living in the old city of Arles since February 1888. In mid-September, after writing to his sister Wilhelmina (or Willemien according to the scripts) that he wanted “now absolutely to paint a starry sky“, he takes action in his Café Terrace, where he shows a small piece of sky dotted with a few stars of the constellation Aquarius.

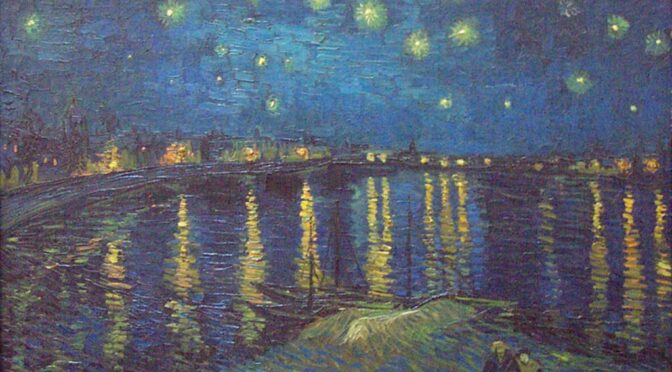

A much wider sky is represented in The starry night over the Rhône, painted shortly after, at the end of September. This 72.5 cm x 92 cm canvas, now on display at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, shows in the foreground, on the bank, a couple seen from the front and moored boats. The silhouettes of roofs and bell towers stand out against the blue of the sky, the city lights reflecting on the river. Among the many stars we recognize in the center the seven stars of the Big Dipper in the constellation Ursa Major, which illuminate a sky in shades of blue. As we will see, the canvas raises more questions than the Café Terrace, due to the incompatibility between the terrestrial view and the celestial view. A detailed survey was conducted in 2012 by photographer Raymond Martinez, see https://raymoonphoto.com/fr/lenigme-du-tableau-2/ (in French) – whose main elements I am adding here with some personal additions.

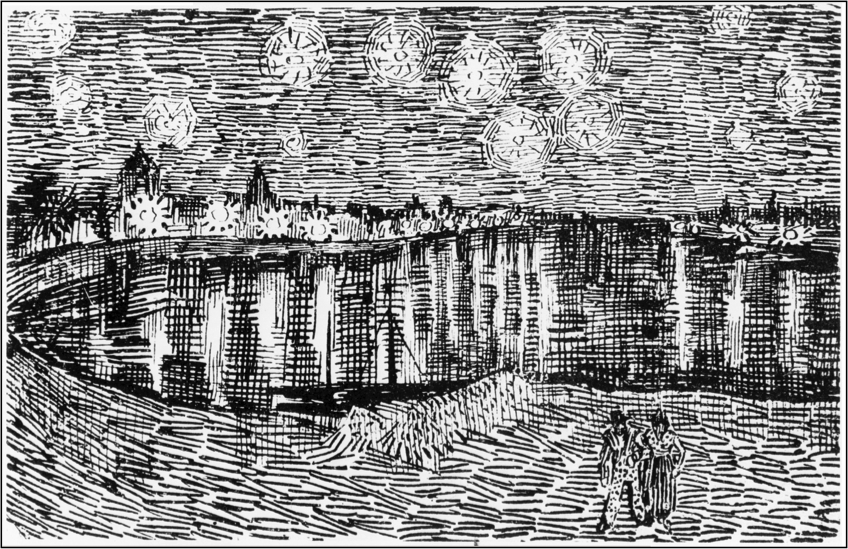

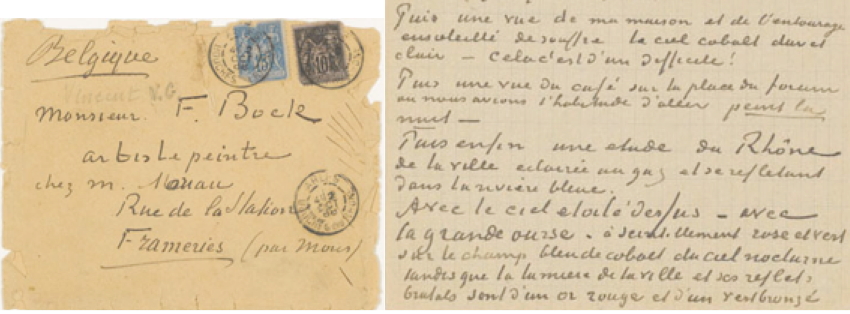

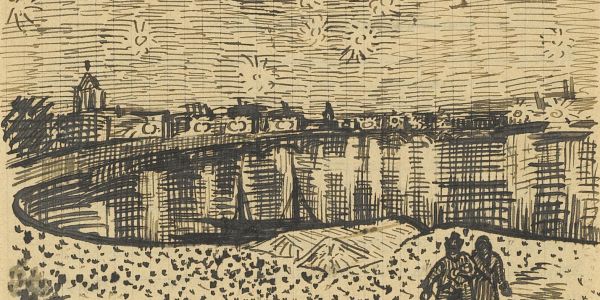

The date of execution is confirmed by a letter addressed to his brother Théo on September 29th, when he has just finished the painting of which he attaches a sketch: ”Included herewith little croquis of a square no. 30 canvas — the starry sky at last, actually painted at night, under a gas-lamp. The sky is green-blue, the water is royal blue, the areas of land are mauve. The town is blue and violet. The gaslight is yellow, and its reflections are red gold and go right down to green bronze. Against the green-blue field of the sky the Great Bear has a green and pink sparkle whose discreet paleness contrasts with the harsh gold of the gaslight. Two small coloured figures of lovers in the foreground.”

On October 2nd, 1888 he sent a slightly different sketch to his painter friend Eugène Boch, with this description: ” And lastly, a study of the Rhône, of the town under gaslight and reflected in the blue river. With the starry sky above — with the Great Bear — with a pink and green sparkle on the cobalt blue field of the night sky, while the light of the town and its harsh reflections are of a red gold and a green tinged with bronze. Painted at night. »

Now let’s look for the place where the painting was done. A sentence from the September 14th letter [Letter 678] to his sister indicates that he certainly painted it on the spot: “Now there’s a painting of night without black. With nothing but beautiful blue, violet and green, and in these surroundings the lighted square is coloured pale sulphur, lemon green. I enormously enjoy painting on the spot at night. In the past they used to draw, and paint the picture from the drawing in the daytime. But I find that it suits me to paint the thing straightaway. It’s quite true that I may take a blue for a green in the dark, a blue lilac for a pink lilac, since you can’t make out the nature of the tone clearly. But it’s the only way of getting away from the conventional black night with a poor, pallid and whitish light, while in fact a mere candle by itself gives us the richest yellows and oranges.“

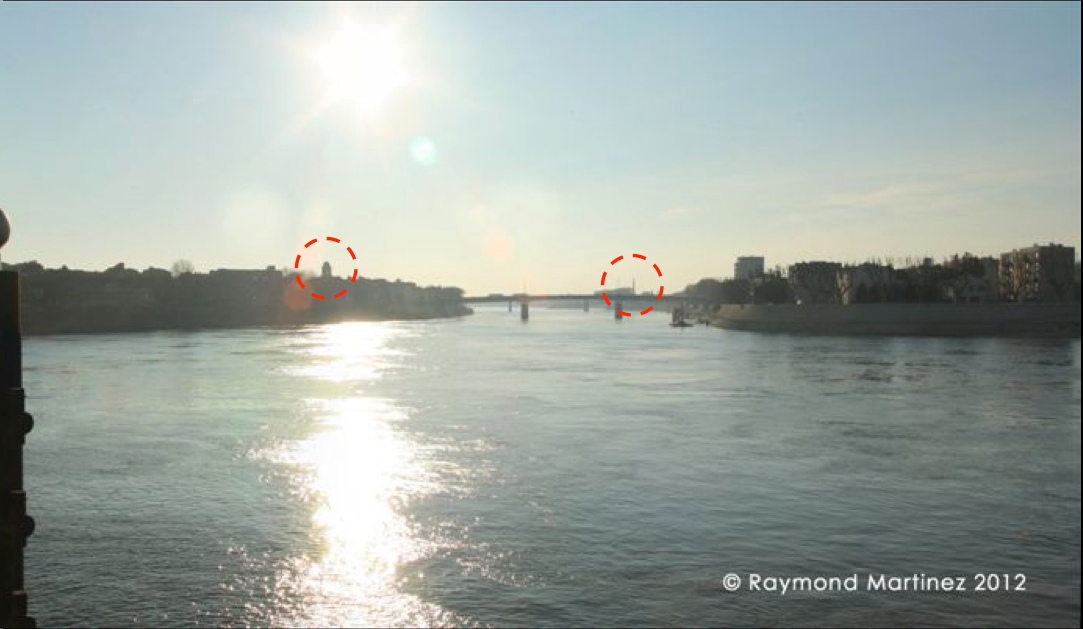

By comparing the current landscape (day and night) with that of the painting, we can spot the exact positioning of the bell towers of the churches of Saint-Julien and Saint-Martin-du-Méjan, the curve of the Rhône on the surface of which, at night, are still reflected the lights of street lamps (now electric, no more gas!), and in the center, the Pont de Trinquetaille:

From this we deduce the very precise location of Van Gogh’s easel and the angle within which the terrestrial landscape is inscribed: the orientation is South-West. Continue reading The Starry Nights of Vincent van Gogh (2) : Starry Night over the Rhône