Sequel of the preceding post Cosmogenesis (3) : Time and Creation

The Creator

The fundamental theological question about the Creation is: who created the universe? The Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity asserts that God comprises three Persons: the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Some theologians have regarded God as the first Person of the Trinity, “the omnipotent Father”, Creator of heaven and earth. Others have focused on the image of the “Spirit of God moving upon the face of the waters” and envisaged the Holy Spirit as the Creator. Others again, in an attempt to reconcile these viewpoints, have maintained that the Holy Trinity itself created the world – a reminder of the Vedic belief in a supreme being incarnated as a single body (Trimurti) with three heads: those of Brahma, Vishnu and Siva.

Album of paintings of Indian gods and rulers, 1831. Paintings with captions in Tamil and French. BNF, Manuscripts, Indian 744.

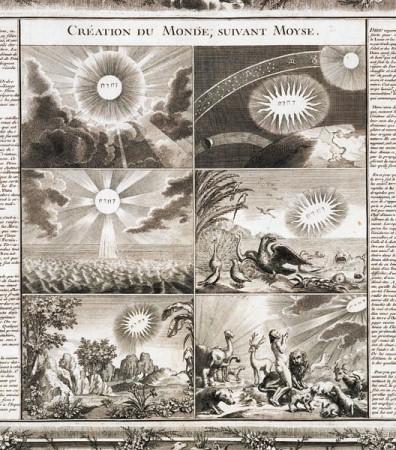

These different theological perspectives are reflected throughout the Middle Ages (in fact right up to the 18th century) in religious art, where one or other interpretation of the Genesis story is illustrated in mosaics, paintings, sculptures, stained glass windows, illuminations and engravings.

The most familiar image of the Creator is the patriarchal figure of the Father (the archetypal example being Michelangelo’s fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel).

Engraving by Raphael Sadeler, in Thesaurus Historia…, 1585

![Young Christ as Creator. The wonderful fresco adorning the cupola of the baptistery of San Giovanni in Padua is the work of the Florentine artist Giusto Dei Menabuoi, who was active in the second half of the 14th century. It shows God the Son as Creator. Giusto Dei Menabuoi, [The Creation of the World], 14th century.](https://blogs.futura-sciences.com/e-luminet/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2016/05/Creation-Menabuoi.jpg)

Giusto Dei Menabuoi, [The Creation of the World], 14th century.

As the Holy Spirit the Creator is represented by a dove (the ancient Christian symbol of the Divine Spirit) – in the work of Robert Fludd, for example – or by the Hebrew word “Jehova” surrounded by a symbol of fire (recalling the burning bush from which Moses received the word of God). In a few cases the Creator is shown as a young Christ figure – in the 13th century mosaics of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice and the 14th century frescos of Giusto Dei Menabuoi in Padua, for example.

The Word and the Deed

Myths about the origin of the universe (cosmogony) generally serve as models for myths about the origin of the gods (theogony), of animals (zoogony), of man (anthropogony), and so on. Mircea Eliade, who has undertaken a study of these myths, points out that one of the most widespread (Siberia, North America, Polynesia, India…) is that of the “cosmogonic dive”, whereby the Creator instructs an animal to dive to the bottom of the ocean and bring Him a handful of clay, from which He models the earth. In most cases the dive is only successful at the third attempt. In many cultures the creation of man follows a similar pattern: the Mayas-Quiches, for example, believed that the gods began by making a statue out of mud and clay; when humidity caused this to disintegrate, they constructed wooden mannequins, but these had no conscience and were oblivious to their Creator; the third attempt was a success when the first human beings were fashioned out of corn meal.

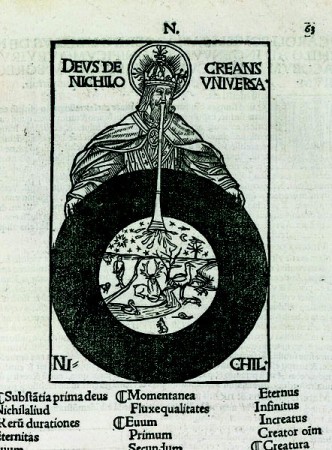

Another category of myth identified by Mircea Eliade is Creation by divine thought, utterance or “exhalation”. An example of this is the earliest of the ancient Egyptian cosmogonies, recorded at Heliopolis as long ago as 2700 BC, which derives from a cult of the sun, manifested as three gods: Ra or Re (the midday sun), Atum (the setting sun) and Khepri (the rising sun). This triple deity, which emerged spontaneously, created the twins Shu (god of air and light) and Tefnut (goddess of humidity), who gave birth to Geb (god of the earth) and Nut (god of the sky), who in turn parented all the other gods. Texts discovered at the pyramids mention two other versions of this story. In the first of them the world is created by expectoration (“Atum-Khepri, […] your spittle became Shu, your saliva became Tefnut”), in the second by ejaculation (“Atum […] grasped his member and the twins Shu and Tefnut came into the world.”). This idea of the world emerging directly from the Creator’s body appears in one form or another in the myths of the North American Indians as well as in the Vedic and Brahmin traditions. Most frequently, however, it is said to be through thought, utterance or exhalation that God breathes life into the world.

Charles de Bouelles, Que Hoc Volumine (Caroli Bovili) Continentur: Liber de Intellectu; Liber de Sensu; Liber de Nichilo, Amiens, 1510.

According to the Sioux Indians, for example, the god Wakonda created the universe by giving physical form to what had previously existed only in his imagination. The Uitoto tribe of Columbia believe that the world was an illusion until the Creator, in a dream, managed to transform it into reality. In the ancient city of Memphis the world was created by the word of the god Ptah, also known as Ta-Tanen (or Tatjenen, Tatunen or Tanen, meaning “One, the maker of mankind”). The Theban priests, in the third millennium BC, attempted to combine the traditions deriving from Heliopolis, Hermopolis and Memphis by attributing to their own god Amon (later united with Re to form Amon-Re) the role of Ptah: “He foretold of things to come and at once they came into being.” Similarly, in ancient India, Brahma broke open the mundane egg with a single word: “The Creator was transformed into a golden egg as brilliant as the sun, from which Brahma himself, father of all things, emerged. He had spent a whole year inside the egg, which he broke in two with a single word. From one half he made the sky and from the other the earth and between them he placed the air, the eight directions of the world and the waters, which became his eternal dwelling place.”[1] The words uttered by the Polynesian god Io, creator of the world, “Let the Waters be divided, let the Heavens be formed, let the Earth be!”, are not dissimilar to those of the Christian God, whose power created the firmament, the waters and the earth.

Pierre le Mangeur (Comestor), Bible historiale, 14th century.

Numbers and Shapes

Like Hesiod’s Theogony, Plato’s Timaeus describes the creation of the cosmos as a process of bringing order and harmony to what was previously formless, but introduces a new idea: that the act of Creation must have been guided by some overriding geometric principle: “When the World began to take shape, at the very beginning, fire, water, earth and air must already have had traces of their characteristic form, but in general they would have remained in the condition which is natural to all things in the absence of God. It was then He who gave all such elements their shape through Ideas and Numbers.”[2]

The idea that the visible world is the manifestation of an underlying mathematical order was taken up by the Neo-Platonist philosophers of the Renaissance and influenced many 17th century thinkers. Thus at the top of the frontispiece to Riccioli’s Almagestum Novum, the hand of God can be seen creating the world according to principles of Number, Measure and Weight (as indicated by the inscriptions at the ends of His fingers).

Bartholomeus Anglicus, Liber de Proprietatibus Rerum, translated by Jean Corbichon.

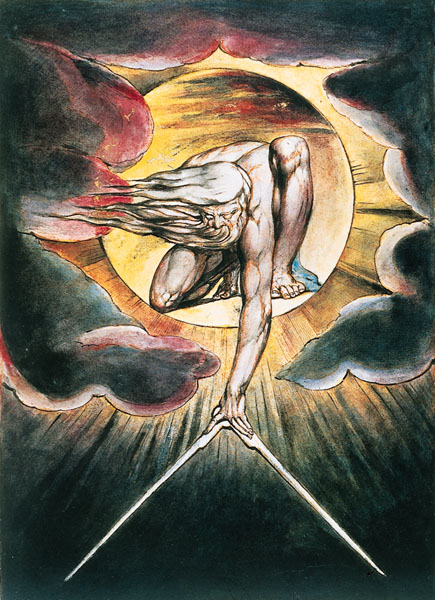

This “geometric Creator” often appears in medieval iconography with a pair of compasses in his hand, as described by Milton in his religious poem Paradise Lost of 1667:

Then stay’d the fervid wheels and in his hand

He took the golden compasses, prepared

In God’s eternal store, to circumscribe

This Universe, and all created things.

One foot he centred, and the other turned

Round through the vast profundity obscure,

And said, “Thus far extend, thus far thy bounds;

This be thy just circumference, O World!”

Thus God the Heaven created, thus the Earth,

Matter unform’d and void.

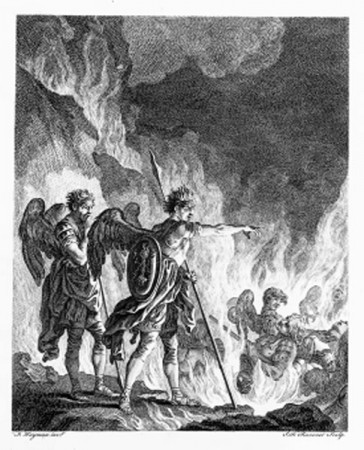

An epic poem in twelve books by John Milton (1608-74), Paradise Lost describes the Fall of man after the original sin and the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. In it Milton tackles the universal theme of the revolt of the angels and the creation of the world by portraying the opposing forces of destruction and creation. For him Chaos is the primeval matter from which God fashioned the world by the manipulation of a pair of compasses and by the power of His Word. In an edition published in London 80 years after the original, the fallen angels are shown being chased from paradise in an engraving by F. Ravenet after F. Hayman.

John Milton, Paradise Lost, a poem in twelve books, London, J. and R. Tonson and S. Draper, 1749.

William Blake, God as an Architect, illustration from The Ancient of Days, 1794.

As science developed, the concept of a mathematically determined Creation became more firmly established. Writing in 1750 Thomas Wright still located a divine creative influence at the centre of each galaxy, but most 18th century cosmogonies played down the role of the Creator. When asked by Napoleon what God’s role was in the Creation, the French mathematician and astronomer Pierre Simon Laplace, author of the monumental Mécanique céleste (1798-1825), replied: “Sire, I find no need to suppose that He had any.” Indeed the Platonic belief that the creation, or at least the construction, of the universe can be described in mathematical terms is still current today, even if we now refer to “group theory” instead of numbers or geometric shapes.

[1] Quoted by K. F. Geldner, ZurKosmogonie des Rig-Veda, Marburg, J. A. Koch, 1908, p. 19.

[2] Translated from Plato, Timaeus, translated by A. Rivaud, Les Belles Lettres, 1925.

****************************************************************