Sequel of the preceding post Cosmogenesis (7) : The Date of the Creation

The Nebular Hypothesis

The ancient Babylonians had a different idea of how the world began. They believed that it had evolved rather than being created instantaneously. Assyrian inscriptions have been found which suggest that the cosmos evolved after the Great Flood and that the animal kingdom originated from earth and water. This idea was at least partially incorporated into a monotheist doctrine and found its way into the sacred texts of the Jews, neighbors and disciples of the Babylonians. It was also taken up by the early Ionian philosophers, including Anaximander and Anaximenes, and by the Stoics and atomists.

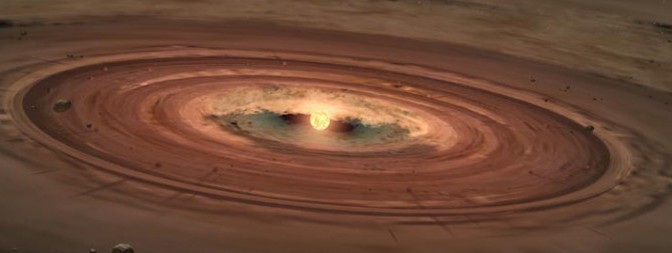

Democritus developed a theory that the world had originated from the void, a vast region in which atoms were swirling in a whirlpool or vortex. The heaviest matter was sucked into the center of the vortex and condensed to form the earth. The lightest matter was thrown to the outside where it revolved so rapidly that it eventually ignited to form the stars and planets. These celestial bodies, as well as the earth itself, were kept in position by centrifugal force. This concept admitted the possibility that the universe contained an infinite number of objects. It also anticipated the 19th century theory of the origin of the solar system, known as the nebular hypothesis, according to which a “primitive nebula” condensed to form the sun and planets.

The idea of universal evolution had a strong influence on classical thought and developed in various directions during Greek and Roman times. In the first century BC Lucretius extended the theories of atomism and evolution to cover every natural phenomenon[i] and argued that all living things originated from earth. Two centuries later, in his medical treatise On the Use of the Parts of the Body[ii], the Greek physician Galen (Claudius Galenus) expressed the essentially Stoic view that matter is eternal and that even God is subject to the laws of nature: contrary to the literal interpretation of the Genesis story, he could not have “formed man from the dust of the ground”; he could only have shaped the dust according to the laws governing the behaviour of matter. The Church Fathers, who insisted that the Creation was instantaneous, rejected any sort of evolutionary theory; to them the ideas of the Stoics and atomists were heretical.

In the second half of the 16th century the idea of universal evolution began to be incorporated into the new system of scientific thought resulting from the work of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Descartes and Newton. According to Descartes, for example, space consisted of “whirlpools” of matter whose motion was governed by the laws of physics. Newton, with his theory of universal attraction, was accused of having substituted gravitation for providence, for having replaced God’s spiritual influence on the cosmos by a material mechanism[iii]. A new view of the world had nevertheless been established, whereby the workings of the universe were subject not to the whim of the Almighty but to the laws of physics – it was an irreversible step. Continue reading Cosmogenesis (8) : The Nebular Hypothesis

![Young Christ as Creator. The wonderful fresco adorning the cupola of the baptistery of San Giovanni in Padua is the work of the Florentine artist Giusto Dei Menabuoi, who was active in the second half of the 14th century. It shows God the Son as Creator. Giusto Dei Menabuoi, [The Creation of the World], 14th century.](https://blogs.futura-sciences.com/e-luminet/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2016/05/Creation-Menabuoi.jpg)